A ‘crossfader’ is a convenient left/right control on the front of most DJ mixers that is invaluable to mixing tracks, since it allows the DJ to control just how much of one song is heard at the same time as another. Move the crossfader all the way over to one side, and only one music source is playing. Slap it back, and the other source is heard. Leave it somewhere in-between, and both songs can be heard simultaneously. An experienced DJ cues up songs generally close in tempo and in the same key, and deftly matches the tempo and beats such that when the slider is moved to the centre, a new song emerges that is a creative, seamless and delightful blend of the two.

This DJ spirit certainly seems to have been at play in Plastikman and Gonzales new collaborative album Consumed In Key, where Plastikman’s 30-year old classic Consumed is the fortunate recipient of Gonzales’ piano interpretations—and the results are stunning. We’ll dive deep into all aspects of the album, but first, a closer look at the uncanny parallelism of the Plastikman/Gonzales timeline.

Sublime Timeline

The people behind the personas, as well as the personas in their own right have much in common. Jason Charles Beck, BMus AKA Chilly Gonzales, and Richard Michael Hawtin, Doctor of Music Technology, honoris causa AKA “Plastikman”, both grew up in Canada in the 1970s and 80s separated by just a 10-hour drive (relatively short in Canadian distances).

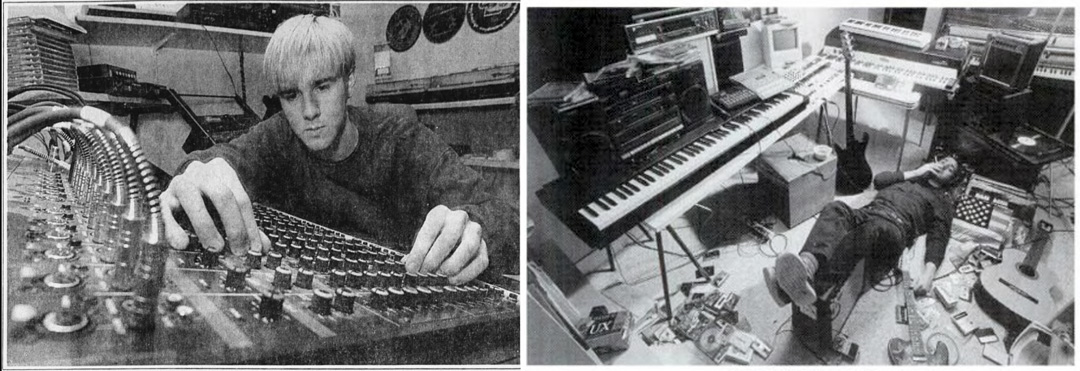

Already standing out in grade school

Already standing out in grade school

Their mothers were teachers, and they had brothers who helped their careers—Gonzales’ brother with honed studio skills, and Plastikman’s brother as DJ and artist. They turned away from major labels and created music publishing companies: Gonzales’ Gentle Threat and Plastikman’s Plus-8—the least of which gave them freedom and ownership over their music. Both changed musical styles while in exile (Gonzales self-imposed in Paris, Plastikman in Canada temporarily banned from entering the US because he lacked a work visa). Plastikman is fast; he’s composed and recoded albums practically in real-time over the course of two days. Gonzales is likely faster, having written entire songs on the train en route to a gig (e.g., an early jazzy number called All Time High—not sure if that’s a drug reference, but it’s possible). Both went through a phase where having a shaved head seemed to at least take the worry out of hairstyles. Purportedly, Gonzales’ hair was also dyed blue at some point.

Both started a single album release (Solo Piano for Gonzales, Sheet One for Plastikman) that turned into a trilogy, and both eventually moved to Berlin in the late 1990s/early 2000s.

They still play, compose, work tour, and show no signs of retiring (although Gonzales did temporarily explore what retirement would feel like on Z, which indirectly led to Solo Piano).

Plastikman and Gonzales in Berlin circa 2002

Six Agrees of Separation

It’s difficult to believe that two people who have had many of the same experiences aren’t also targeting the same audience, yet their Venn circles seem to barely overlap. There’s a fairly significant difference between a Plastikman playing a 12-hour set to drug-induced partygoers, and Gonzales mixing piano with rap and bongos, to sold-out sit-down patrons in a regal concert hall. Plastikman and Gonzales do have more in common than one would think, and that’s a good starting point for examining how they finally came to cross paths to arrive at the sublime Consumed In Key.

When I’m an artist, … I work in an abstract musical world, I don’t think of people, places, song titles, concepts, or even what musical tools I may be using.

- Chilly Gonzales

It’s not the tool, it’s like what your intention is, and if you’re actually channeling something from deep within you, through that apparatus and coming up with something unique at the end.

- Plastikman

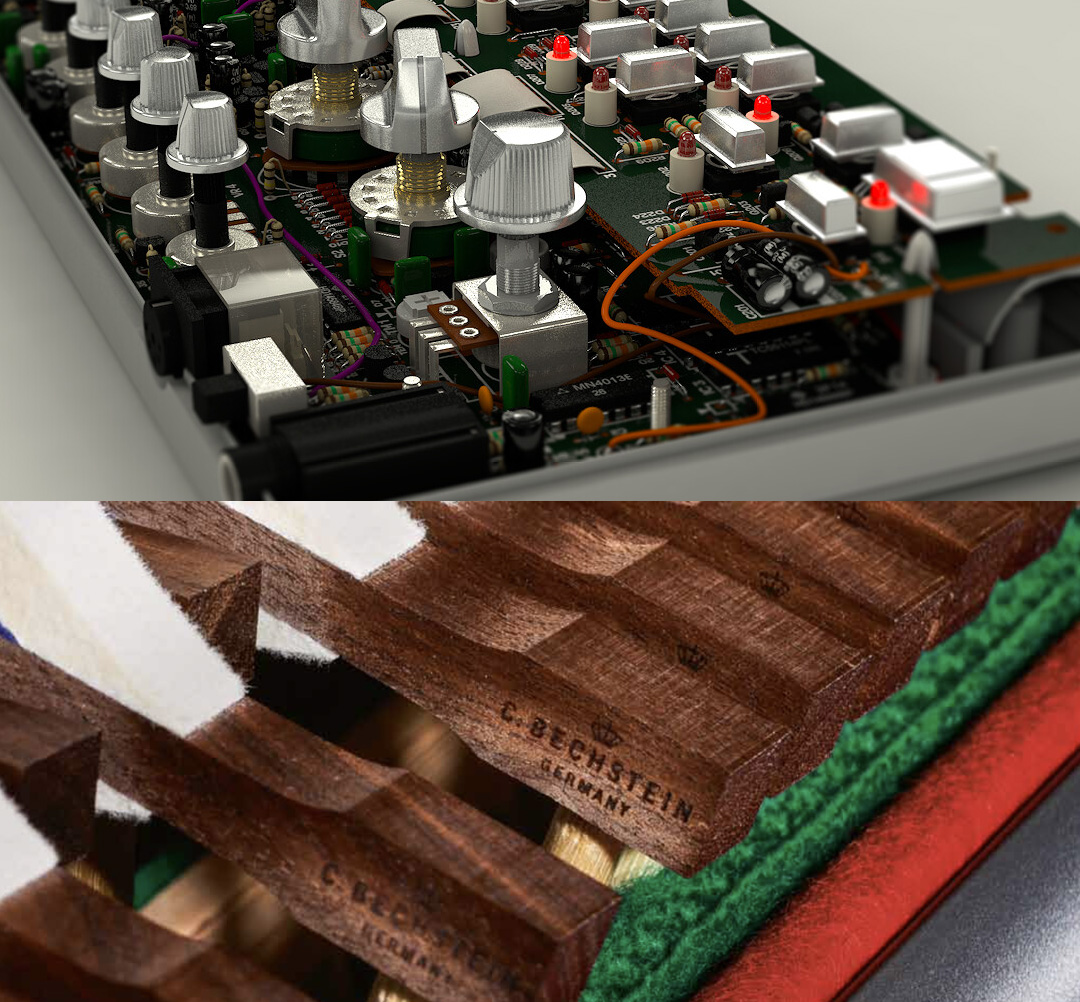

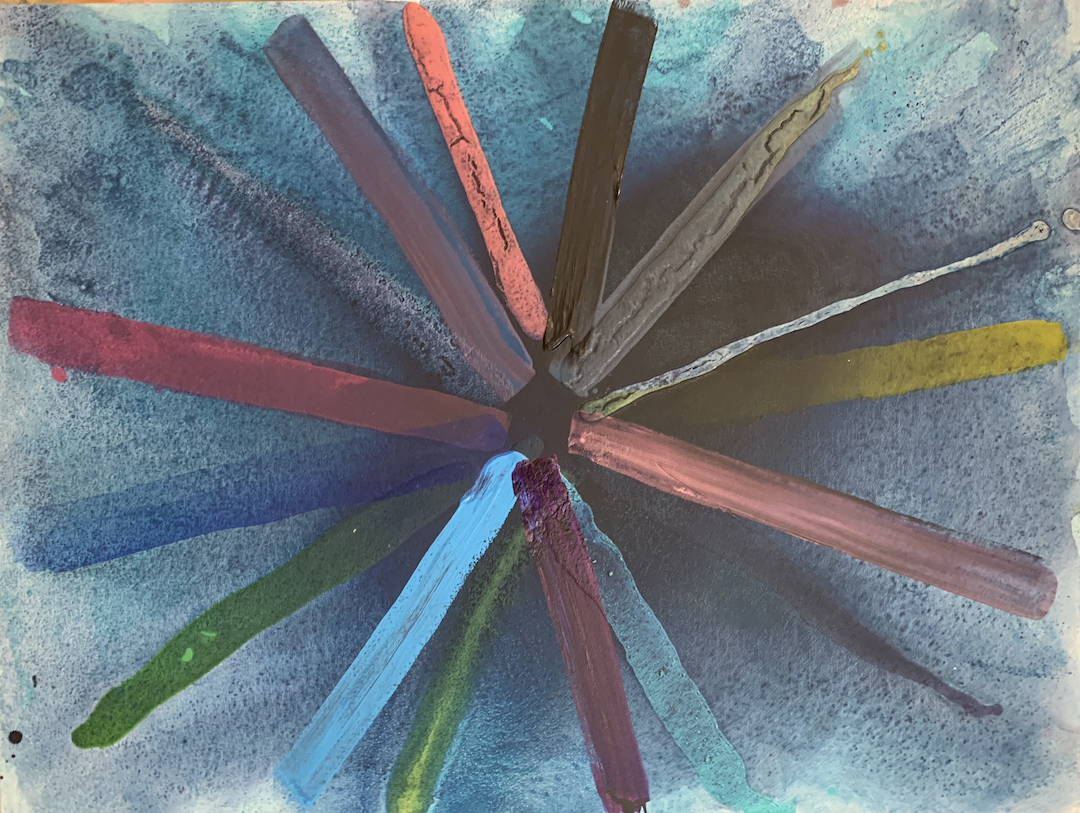

TB-303 and Bechstein Action detail

No matter where one looks, it appears that these two musicians and entertainers have been separated by a thin thread for almost 40 years. When wondering what the hype sticker would be for Consumed In Key (turns out the album doesn’t have one), the first search result for “hype stickers” was an exhibit in Cologne, including Plastikman, but just below it, Jamie Lidell’s Multiply, which Gonzales played electric piano, bass synthesizer, bells and piano on. The original Consumed had a peelable sticker with just the album name—supposedly because the cover was a dark rectangle on a dark background. Gonzales’ hype stickers range from magazine quotes: “Expect great things – NME” on Über Alles, to “The misunderstood masterpiece” on Soft Power, and “The new official Gonzales album!”, on The Entertainist (still looking for the “unofficial » album).

Back in Vantablack

As you know, we love album design, and Consumed In Key certainly didn’t escape our attention.

The original Consumed release had a die-cut rectangle centered within a dull black cover, revealing the violet album sleeve inside.

The 3xLP cover for Consumed In Key also features a die-cut rectangle, but this time in a white cover, revealing a black album sleeve with a centred embossed black glossy rectangle.

The rectangle may be an allusion to the monolith in Arthur C. Clarke’s novel 2001, which represented notable transitions in the evolution of humans–and is in a sense, an alien ‘tool’—the purpose of which is to advance life throughout the galaxy. From a literaly etymological perspective, the rectangular shape of the monolith was inspired by the oar Odysseus was to plant upright when he encountered inland people who had no knowledge of Poseidon’s Sea kingdom; in this way, Odysseus could educate people and spread knowledge. Using a cutout adds cost to any album cover—it has to impart something more than just a neat effect, and in the case of Consumed and Consumed In Key, we’re looking through a narrow window, but there’s only darkness on the other side of the window. There’s a special black substance called Vantablack, which absorbs 99.965% of the light striking it. So black in fact, that it’s deeply unsettling to anyone who looks at it—almost as if there’s something wrong with the universe on those surfaces. All these ideas elicit Nietzsche’s quote, if you gaze into the abyss, the abyss gazes also into you, which is reminiscent of an interview in which Mr. Hawtin explained the original album’s genesis in a cabin in Northern Michigan.

Being out of the city, you can see the stars, but it’s just pitch black. Walking away from the lodge, you could see the light in the distance. And you got to a point where you’re in the forest, in a clearing, and that light disappeared. Which was your only light source to the regular world. And then it just became darkness, the blackest black you’ve ever known. You couldn’t tell where sounds were coming from, what they were, how those sounds were distorting. You didn’t know if there was someone next to you, or if there wasn’t. You didn’t know if the next step was on the end of the hill or if it would take you straight into a tree. It was how I would now describe my album. Because it’s the same kind of feeling. This space that we were locked in—I was with my girlfriend and she was holding my hand, but as soon as we lost touch you were a thousand miles away—it was like something some people would consider an eternity. That ties in with the album. It’s about a real mood, it’s not about one track above another, it’s about letting yourself be consumed into that atmosphere, it’s about having enough space to really climb into the beats.

As it turns out, since Vantablack is not a pigment but a substance up for sale, the artist Anish Kapoor purchased exclusive worldwide rights to use Vantablack as an artistic medium—much to the dismay of the rest of the art world. In many interviews, Plastikman indicated that Kapoor’s art was partially the inspiration behind Consumed.

Anish Kapoor has been a major influence on my work since the 1998 Plastikman album Consumed. The subtlety of colour, perception and dimension in his work has always intrigued me, reminding me of the way I think about the acoustic characteristics of my own work.

- Plastikman

The Holocaust Memorial, 1996, Anish Kapoor

On Consumed and Consumed In Key, artwork credits are attributed to Rich, Math, and Sean, with Math being Matthew—Plastikman’s brother. In an interview on album art, Matthew said, “I work with simple elements to express ideas but behind that there’s usually some emotional value I’ve been considering.” Gonzales’ Solo Piano series is praised for providing enough space for people to add their own emotions and feelings and make the songs personal, and on Consumed, it apparently was Plastikman’s goal to provide a vehicle that could carry personal thoughts and emotions as opposed to ‘telling’ people what to think.

I prefer room to breathe in my music, room to think. To see and hear the spaces as much as the sound.

- Plastikman

Although the cover for Consumed In Key has changed from dark grey to white, there’s a great side-effect (by design) in that it now appears as a glossy black piano key in the midst of a sea of white keys. Of course, Gonzales has extolled the virtues of minor keys, both in interviews and musically, since black keys unlock melancholy and sadness as opposed to the accessible and celebratory nature of white keys. On Self Portrait from The Unspeakable Chilly Gonzales, Gonzales tries to, “avoid the void but it’s just there,” referring less to empty space, and more towards looking back at his own persona and possibly trying to figure out who’s looking at who. As listeners, we’re looking into the abyss of two artists, and the obvious question is whether or not having one fill in the space left by another ‘consumes’ room for thought, or do the new sounds add another dimension of exploration? As the record starts, an unseen hand slowly moves the crossfader away from Plastikman towards the middle…the sound of Gonzales’ piano starts to envelop us…

Crossfader: Centred

Normally, we’d have a detailed song-by-song review, but we’ll save that for another article; Gonzales’ piano is always a special treat, and the additions to each track were uniquely crafted with obviously a great deal of thought. Here’s a ‘teaser’ with some of our initial musical notes jotted down from listening sessions:

Contain

Gonzales heightens the tension with high-register sequences that fade in-and-out analogous to the filter knob on a synth, but amazingly, on a piano. Grace notes abound before the sequences are connected into gentle chords. Eventually, Gonzales settles on a back-and-forth drumming rhythm in high registers where reverse-piano effects are interspersed. The gentle ending is reminiscent of rain softly falling.

Consume

Opens with funky ‘hits’ that you’d normally hear as horns, but they’re on piano. Turns into a lilting passage around the 6:30 mark, with uplifting piano matching the feel of the original string synthesizer. The end is classic Gonzales; a beautiful melody that sounds like a song onto itself, but compliments the original track perfectly.

Cor Ten

Starts off with rolled chords like only Gonzales can; it’s more Gonzales than Plastikman at this point, but then the see-saw rhythm kicks in, which adds a vaudevillian flair and changes the mood. By then end, the piano and synth sounds as if it could easily mix into an Octave Minds track.

Ekko

Soundtrack-y…Gonzales used to provide a live soundtrack to silent movie night in Berlin; can easily imagine him visualizing the song and employing reactionary playing against it (can you soundtrack against what’s in your mind’s eye?) The soft melodica is classic Gonzales. Pulsating and with the accent on Plastikman’s TB-303, the tension is increased but ultimately fades and remains unresolved. Luckily, Gonzales’ piano rolls and melodica float away with us.

Converge

One-two-three counts off Gonzales’ piano, while a synthesized choir ‘aahhs’ in the background. Small rising keyboard sequences are played on select octaves, eventually morphing into a classic Gonzales melody with Plastikman’s soft brass ‘wah-wahs’ dancing around the piano layers. Lots of movement on this track; fantastic.

Locomotion

Starts with organic chord ‘hits’ timed to the bass drum. Then, once the Yello-like TB-303 bass ‘motion’ sequence is off and running, it becomes a bit of a race between synthesizer and piano. Descending chord sequences move from sad to almost samba-like dance moves, with two- and four- note arpeggios competing for our attention. Gonzales employs an Autobahn-style piano effect as if he’s passing by the listener. An incredible track; definitely a highlight.

In Side

A pensive and hesitant melody are set to a relentless kick drum, then the melody moves up to a higher register while dreamy, soft tremolo can be heard (is that Stella’s cello joining in?). The track is replete with soft background piano chords that add to the eerie ambience. Somehow hear echoes of Headstone Park from Presidential Suite in the song (must be the cello). The synthesizer and piano tussle a bit, but eventually switch places, becoming more piano-centric at the end. Could definitely see Gonzales play an expanded version of In Side in concert.

Consumed

Starts off with a Durutti Column-like sequence setting the track in motion, then Gonzales arrives with wide piano sequences, which are overlaid with thematic pizzicato-like piano hits. Tension builds and eventually, Gonzales introduces a parallel melodic sequence; piano layers build and are taken away. As the acid TB-303 drops in tone, the entire track distorts and fades until Gonzales brings us back from the brink. Beautiful fade on a gentle track.

The fascinating part of Consumed In Key is that it makes you feel like a kid; repeated listens remain interesting with many rooms to explore. Gonzales mentioned that he’s happy to be music that’s front-and-centre, and equally happy to be background music, and this album definitely fits the bill for both—depending on your mood and whether you need to let your mind wander and dream, or are looking for inspirational ambiance. It’s the kind of album that people visiting will stop and ask you, « Whose album are you playing? », followed by a great conversation.

Analogue Pedagogue

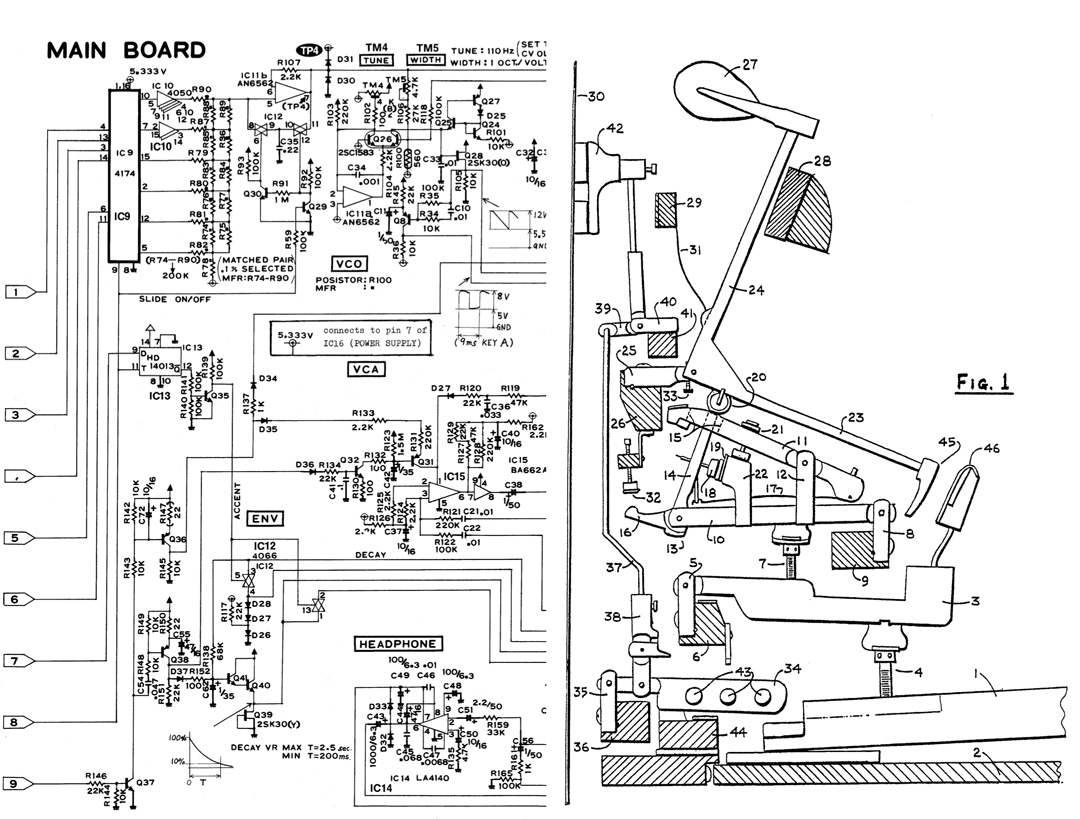

In recent interviews, Plastikman said he felt ‘challenged’ during the mixing of Consumed In Key, not having dealt with bringing the idiosyncrasies of acoustical instruments into the final album. The piano is certainly an analog stringed and percussive instrument, with a high degree of complexity and many moving parts (almost 10,000), while Plastikman’s Roland TB-303 (the instrument primarily featured on Consumed) has only a few hundred parts, yet is actually an analog instrument at its core. There are no samples, virtual instruments, or acoustic modelling techniques– just analog oscillators, amplifiers and filters producing a sound originally designed to provide bass accompaniment, although it disappointed in that regard, and was originally considered a failure by Roland. Several years after it was discontinued by Roland, Chicago- and Detroit-based musicians started using the TB-303 in unconventional ways, partly made possible by the very same design shortcomings that made the TB-303 unsuitable for bass accompaniment. Unknown at the time, in 1982, the late Indian musician Charanjit Singh created one of the first albums called Synthesizing: Ten Ragas To A Disco Beat, which paired the TB-303 with dance music and predated the Chicago and Detroit sounds by six years.

TB-303 vs. Upright « Mechanisms »

As Gonzales fans will know, his love for piano was fostered by his grandfather who emigrated from Hungary to Canada in the 1940s (not by choice) and continued to hold classical music in high regard—a sentiment his grandfather passed along. After a stint on drums and guitar, Gonzales re-discovered the piano and studied musically formally, although Gonzales is no stranger to the technological aspects of music. In a Gonzales interview some time ago, he credited a high school teacher with setting up time to sit in on a recording session with the then-popular Canadian band “The Arrows”. In the studio, Gonzales played with the latest synthesizers, which may have included an Emulator III and Roland products. When Gonzales completed university, his band “Son” (JaSON, or “son”, which means sound in French—it’s a name that works on many levels—also in “son de blé”, or “wheat bran”, but it’s unlikely he had that in mind in his youth), embraced synthesizers, with Gonzales often found playing a controller on stage, plus there’s also the publicity photo in his basement studio surrounded by keyboards and recording equipment; unsurprisingly, the piano at the back of the room has already shed its cover.

Surrounded by the warmth of technology

Even early Gonzales featured a multitude of electronic sounds, many of which Gonzales obviously mastered and likely found interesting, but (and this is only a guess) he realized that he was spending more time learning and dealing with technology than actually composing music. In the not-so-distant future, everyone was going to have access to a multitude of instruments and sounds, and it was going to be difficult to set himself apart. Enter the piano, and no matter how amazing Alice Sara Ott sounds (and she sounds great), her rendition of Gonzales’ Prelude in C Sharp Major lacks the jazzy soul that only Gonzales can inject. We’ve never heard a recording of Beethoven playing piano, so there’s nothing that could be considered the gold master to compare against, whereas Gonzales’ intent and style (recorded or live) is very much apparent, and we naturally compare subsequent attempts to his originals. When Gonzales returned to electronic music in Ivory Tower and Octave Minds, he outsourced the electronics to Boys Noize, while he stuck to piano.

All of this isn’t to pit piano against synth, but rather demonstrate that Gonzales has been combining synth and piano from practically day one as a musician and composer—he’s obviously acutely aware of the limitations of both and can play to the strengths of each one. The challenge in Consumed In Key was likely not having any say whatsoever on the electronic “side” of the music, but how to reinforce existing sounds and create a new work that captures the imagination of listeners—including fans of both artists, and people hearing Plastikman and Gonzales for the first time.

Plastikman and Gonzales with their instruments of choice

While in Berlin around the turn of the century, Gonzales regularly played piano for silent movies and in hotel lounges, and he’s composed and performed music for films such as The Piano Room, Could This be Love?, and even earlier for Isaac’s Fables. On Consumed In Key, it often sounds as if Gonzales is visualizing a movie he’s composing the soundtrack to—but of course, the movie is actually Consumed, and he’s playing along as he’s visualizing. In some sense, we’re hearing what Gonzales is ‘seeing’ while he’s listening to Consumed, and the results are captivating.

Shadows and Light

Plastikman’s moniker, as the story goes, came about because of his penchant for wrapping rave venues in black plastic; objects wrapped in plastic or fabric can be transformed into works of art, as evidenced by the grand artwork of Christo and Jeanne-Claude. The sonic black plastic shadows heard in Plastikman’s Consumed seem to repent a “primordial soup” of sound—where concentration is required to hear changes in long and slowly evolving passages. Going from a world of different sounds to the single-mindedness of Consumed takes one from light to dark—you have to squint at first to make anything out, then relax and let your pupils open and eyes/brain acclimatize to the darkness. Sometimes, you see random lights and patterns from your brain—almost as if it’s trying to fill the void—peering through the slit in the album cover and something much deeper. Once you open your ears to the experience, you realize that you’ve been listening to music in Plato’s Cave, and what you’ve heard up until this point are shadows of what the music industry has been projecting onto the cave wall. Once free of your limited hearing, you realize that there’s an entire universe of sound, and fumble in the darkness to reach the source.

Just then, Gonzales’ piano appears out of the shadows—subtle at first, as if hearing him beckon from around the corner. Curious, you walk over to have a closer look; the soundscape opens up as you approach, and you begin to understand.

When Marty McFly played Van Halen to his ‘younger’ father from a Walkman in Back to the Future, his father didn’t understand what he was hearing—his brain couldn’t process the sound, since he hadn’t been previously exposed to it. When we exit the cave and first hear Consumed In Key, it’s initially difficult to discern what’s happening—we rationalize the sounds against the ‘shadows’ of sound we were previously exposed to. It’s as if someone from the future came back to us and asked if we understood how music will change and evolve when there’s no central ‘authority. Gonzales understood, but his musical mind, training, and experience allows him to hear and ‘see’ music in ways we don’t (and likely can’t). Many of us will run back to the familiar sanctity of the cave, content with listening to familiar shadows, since that’s the reality the majority of people know and have been exposed to since birth. With subtle, familiar, and lush piano, Gonzales’ accompaniment gives us a sense of ‘centre’ within an album that, although it’s Plastikman’s best-selling album, remains an enigma to many. Gonzales is acting as a musical Rosetta Stone, translating Plastikman’s sounds into melodies and interpreting it for us—yes, in his deeply emotional style, but we’re free to revisit the original Consumed to create our own version at any time.

There’s a great early comment somewhere in the cosmos of the internet that responds to someone asking, “Where’s the music on Consumed?” The retort is akin to John Cage’s 4’22 in that the music is, “Whatever isn’t nailed down in your living room, since it happily rattles along with Consumed’s bass frequencies.” In this sense, the album can be unique in every listening environment—the absence of overt melodies or voice is replaced by the unique rattling and buzzing throughout your home or car. There’s another insightful review of Consumed that needs little explanation and largely sums up the sentiment just explored, “Absolutely sublime. Rich, resonant traces of music, so sparse yet so full. This goes beyond emotion, it goes beyond comprehension. It transcends all…this is the music God gets funky to.”

Prior to Consumed, Plasktikman (under the alias of “Richie Hawtin”) worked with the late Pete Namlook on a series of ambient instrumental albums called From Within, which were highly acclaimed, as evidenced by a quote from the Toronto Star:

Together, Namlook and Hawtin conjure a series of long, softly swelling cosmic mood pieces that rely on drawn-out dynamic shifts and suggested, almost subliminal rhythms for momentum.

One track in particular, A Million Miles to Earth, features an (obviously sampled) piano in its first few minutes (the track is almost 30 minutes long). Based on Plastikman’s previous experimentation with piano and ambient techno, it’s easy to see why he’d be open to Consumed In Key—he likely knew Gonzales’ piano would make Consumed more accessible to a wider audience. Tiga, who executive produced the album, must have also heard a mix of Plastikman and Gonzales in his head, and we’re fortunate that he persevered and saw Consumed In Key through to fruition.

Abstract Heart

Gonzales always manages to give great interviews—even though he’s been through thousands, he always seems to dynamically throw in something new. A few years ago, he explained an experience from his youth that seems to have stuck with (and motivated) him:

I remember going to art galleries with my father as a kid and seeing him feel sort of threatened by abstract art. The minute he couldn’t tell what was literally being represented in a painting, he was a bit like, “Ugh, I don’t know how to react to that! …He would go and read the little card next to the painting and it would say something about Mark Rothko going through a divorce when he painted this and all of a sudden, I could see my father’s body language change. “Oh, now I understand how I’m supposed let this piece of art have its effect.

Untitled, 1968, Mark Rothko

Oddly enough, besides Kapoor, Plastikman indicated that Mark Rothko was also an inspiration behind Consumed.

Most people are somewhat like Gonzales’ father in that we appreciate stories behind things that are initially enigmatic—we’re curious creatures by nature and love to know why things are the way they are. In Consumed In Key, Gonzales provides us with that little card beside each track—we hear his familiar melodies and chords set against an abstract background, and that’s the story that allows us to say, “Aha!”—I appreciate the music much more than I did before.

The sculptor Anish Kapoor, who we discussed previously, seems to have a gift of providing insightful quotes:

I don’t want to do what I did before, I want to do what I just don’t know how to do.

In a similar vein, Gonzales previously stated that,

I fearlessly try different styles to explore what happens when you have X and Y interact. Whereas [Richard] Wagner would say no, both should stay in their proper corners of the sandbox.

It’s this sense of adventure; going against what other people think (specifically, doing the opposite of someone such as Wagner) and not repeating the same process, since it doesn’t seem to provide enough personal growth for Gonzales; he must move on, even though it’s likely uncomfortable and a bit scary. That spirit is what may have convinced Gonzales to combine his sublime piano with Plastikman’s dark soundscapes (that, and it’s highly likely that Tiga is very, very convincing).

The other Kapoor quote strikes at the heart of Contained and Contained In Key:

The void (…) has many presences. Its presence as fear is towards the loss of the self, from a non-object to a non-self. The void does not really exist because we are constantly filling it with our expectations and fears. My sculptures that are called empty objects therefore contain a possibility. They stimulate a philosophical thought but are not the answer to anything. They simply present a condition; you have to do the rest.

Gonzales, Kapoor and Plastikman appear to love to explore a void, since a void can never truly exist, and furthermore, it’s unique to each person viewing or listening to it. This concept is certainly not new to Gonzales—as we’ve discussed many times, the space Gonzales leaves in his music is for us to fill and make personal. Even after Gonzales provides his interpretation of Plastikman’s sonic void on Consumed In Key, there’s still a great deal of sonic space for us to fill in and make personal, and some would say that Gonzales (like his father and art) helps to make Plastikman’s music even more personal and enjoyable. Gonzales’ gift, like many abstract artists and sculptors, is helping people create their own personal message. He’s more successful at art through skill and taking chances—bringing us deep and personal emotions, and it’s clear that Gonzales has much more to explore in this regard.

The last word on the ‘art’ side of Consumed In Key belongs to Feist’s late father, who was a celebrated Canadian artist, and, like many artists, the depth of his work will be discovered for years. In an interview, he was asked how he approaches art, and replied that to him, art is, ‘putting something good into the world.’

Harold Feist: Proponos, 2016

In the Wink of an Eye

There’s science fiction story from the 1960s where aliens live among us, but only within the tiny fractions of a second between our seconds—almost as if they are in an undetectable parallel universe, yet they could see everything we were doing, but in slow motion. The lifeforms eventually used their speed and ability to help humans, and humans helped the aliens evolve into a species who could communicate with other life forms. In some sense, Gonzales added his compositions ‘in between’ Plastikman’s moments—two separate compositions living together and reinforcing the emotion and power of each.

Gonzales and Plastikman standing on a large crossfader

One recent interview (and there appears to have been many for Contained In Key) asked if Gonzales’ contributions were akin to drawing a moustache on a painting; the ‘Bansky’ of the music world. More appropriately, Gonzales’ emotional contributions paint within the blank spaces on Plastikman’s canvas to create a new work of art that adds rather than detracts from the original—helping listeners to see the whole in a new light. When X-rays were used to analyze paintings, some surprising discoveries were made, including hidden paintings underneath famous paintings. There were also paintings discovered to have had ‘additions’ by subsequent artists, including The Armorer’s Shop by David Teniers the Younger with a previously unknown addition (a pile of armor) by Jan Brueghel the Younger approximately 20 years later.

The Armorers Shop – replete with a new and exciting pile of armor

Up until this discovery, the world saw the Teniers painting as one as opposed to two separate paintings and enjoyed both. Adding to prior art sometimes updates or reinforces the original message and brings it to a new audience—technological advancements have made this ability to update art available to many more creative minds than would have been possible even 50 years ago. It would be an interesting experiment to have painters purposely leave ‘space’ in their canvases for subsequent artists to ‘fill in’ as subsequent generations of artists brought their vision to the painting. Of course, works of art over the centuries have been altered for censorship to align with societal, lawful, or religious codes of the day, but these have largely taken away from the original as opposed to enhancing the meaning of the piece.

Besides the personal and introspective nature of the music itself, Gonzales mentions the concept of “urtext”, which is essentially a printed copy of sheet music with the original intent of the composer reproduced as accurately as possible. Traditional difficulties include handwritten manuscripts, missing pieces, post-performance changes among many others. With Consumed, as with any post-recording technology music, the intent of the composer has been captured by the composer themselves. Gonzales has the original music plus composer intent and can work directly from that alone, or even reach out to the composer himself to ask questions (which he apparently did not—unwilling to bias his interpretation).

With further advances in technology, the question of whether a record will still be a ‘record’ (i.e., a point-in-time recording) appears, meaning that the listener’s musical preferences will influence the composition itself in real time. Dynamically composed and tailored music to suit a listener’s musical taste will leap past a customized playlist to ensure music can be modified to suit the listener. Gonzales regularly demonstrates this effect to some degree by dynamically changing his playing style to suit the audience’s mood: extra boisterous? Gonzales lays into a 12-minute rendition of Dot that resonates with everything and everyone. Seemingly laid back? Gonzales plays a shorter, more playful version of Dot and segues into Kenaston. Most DJs are familiar with “reading the floor”—knowing when it’s time to maintain, speed-up, or slow down the tempo, and what style (or even key) of music the audience prefers and reacts positively to. In this sense, Gonzales is the ultimate DJ—and in Contained In Key, he moves the crossfader with a sense of deftness and dexterity only he could manage.

Impress Yourself

The slowly changing and morphing sonic landscapes on Consumed In Key are somewhat akin to Gonzales’ piano trilogy—only the changes on Gonzales’ Solo Piano style take place over the course of 14 years as opposed to 8 minutes. What we witnessed was the evolution of Gonzales initially bringing the exuberance of youth and 3-minute pop song to Solo Piano, to a sophomoric sophistication in Solo Piano II, to the incredible depth and confidence in Solo Piano III. Although some of the songs on Consumed In Key sound as if they aren’t changing, the gaps and subtle morphing over time provide just the right amount of space and evolution on which Gonzales could build his piano patterns, chords and melodies on. In the same way, Gonzales filled in the gaps in his own past, and played against his ‘ghost’ to move forward as an artist and entertainer, which helped his music reach a wider audience.

Consumed In Key inspires you to use the ‘space’ you’ve been given wisely; dream up new ideas that are harmonious with the wonderful people and beautiful things around you. Have the confidence to cue a new disc, move your own crossfader to the middle and come up with a sublime new song in your life—show people what you’re capable of, and interpret the world around you in a new way. Question if you’ve been watching other people’s shadows too long, and leverage your past to change the present and future for the better. Like Gonzales’ piano on Consumed In Key, it takes skill, courage, and experience to create beautiful new art on a seemingly static and unchangeable past.