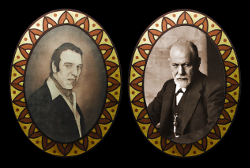

It’s curious how a concert can be construed as a therapy session en-masse with characters on both sides of the stage divide standing to benefit. The “psychologist” wears comfortable slippers and sits on a padded leather chair. He or she has a bevy of tools at hand for eliciting responses from audiences, including musical instruments, voice, other musicians, and willing (and not-so-willing) audience members. In North America, traveling illusionists such as “The Amazing Kreskin” or the late “Reveen”, blur the lines between entertainer, therapist, and illusionist, often employing therapy or other devices to not only entertain, but also to make grand statements on the nature of consciousness and one’s ability to believe. In honour of the oft-overlooked role of entertainer as therapist, we invited the father of psychotherapy – Sigmund Freud himself – to ‘analyse’ the 12 distinct personalities on Chambers. Not that the compositions require any therapy, but rather, the act of thinking about the compositions in a deep manner may elicit thoughts and ideas that are applicable to other aspects of life. We hope you enjoy his review.

It’s curious how a concert can be construed as a therapy session en-masse with characters on both sides of the stage divide standing to benefit. The “psychologist” wears comfortable slippers and sits on a padded leather chair. He or she has a bevy of tools at hand for eliciting responses from audiences, including musical instruments, voice, other musicians, and willing (and not-so-willing) audience members. In North America, traveling illusionists such as “The Amazing Kreskin” or the late “Reveen”, blur the lines between entertainer, therapist, and illusionist, often employing therapy or other devices to not only entertain, but also to make grand statements on the nature of consciousness and one’s ability to believe. In honour of the oft-overlooked role of entertainer as therapist, we invited the father of psychotherapy – Sigmund Freud himself – to ‘analyse’ the 12 distinct personalities on Chambers. Not that the compositions require any therapy, but rather, the act of thinking about the compositions in a deep manner may elicit thoughts and ideas that are applicable to other aspects of life. We hope you enjoy his review.

Dr. Sigm. Freud

20 Maresfield Gardens

London, England

United Kingdom

I’ve long regarded music as my competition, and (as such) it shouldn’t surprise anyone that listening to music makes me uneasy. Besides being completely non-musical, I don’t particularly care to be moved emotionally by a mysterious and deep-rooted force without my cognitive consent. According to Theodor (one of my students), music likely has power similar to that of psychotherapy, and he postulates that feelings can be more accurately represented though music than words alone. I’m not completely ambivalent to pleasurable sensations of music; I do enjoy a good opera – Verdi and Puccini in particular, but many are quick to point out that I concentrate on the libretto and tend to ignore the accompanying music altogether. My core belief follows Kant, in that visual stimuli (e.g. dreams and art) reveal far more about latent meanings than auditory stimuli, and comprise the bulk of my psychoanalytic theory. In sharp contrast, one of Theodor’s latest theories is that unconscious feelings and memories manifest themselves as melodies due to the closely related nature of music and emotion. I am aware of his experiments to resolve repressed conflict with music therapy, and I have to admit that I am more than curious as to how he has concluded that words obscure where music reveals. My initial reaction is that music can be just as manipulative as words – if not more so. In theory, if music is indeed more powerful than words, a skilled composer could falsely impart emotions and moods that they themselves or their listeners have never experienced or felt before. If Theodor’s theory were true, the power to impart emotions through music would seem to be more ‘dangerous’ than mere words alone.

It was my appetite for scientific discovery that led me to (somewhat reluctantly) to listen to a performance of Chambers by the Canadian composer “Chilly Gonzales”, which Theodor purchased on six 12-inch records. I wore my usual slippers, and found a location where I could listen and write comfortably. What follows are my consolidated composition-by-composition notes and psychoanalytic theories on the nature of Mr. Gonzales’ performance, how his music affects the listener, and what conclusions can be inferred.

Prelude to a Feud

I use hypnosis as a psychotherapeutic technique on a regular basis, as I find it to be a fundamental tool in the psychotherapists’ tool chest. The initial ascending piano sequence in Prelude to a Feud is reminiscent of a pre-hypnotic state, where the ascending sequence is repeated over and over again, lulling the listeners into a state of relaxation. After the elegant harp-like sequences, the piano seamlessly moves to the harmonic and rhythmic cadence of a stately leitmotif somewhat reminiscent of a march. Soon, the string musicians imitate the piano march in perfect reproduction. In a sense, they have received the ‘orders’ and are absolutely willing and able to carry them out to perfection. Repeating a melody is akin to requesting to hear a story again and again as children tend to do; the infant ego seeks a challenge to complete a familiar journey and navigate conflicts in preparation for adult life. As adults, we find comfort in repetition and are somewhat taken aback when presented with unexpected situations. Popular songs have capitalized on our innate desire for repetition and comfort, as opposed to the apparent lack of humanity inherent in atonal music by contemporary composers such as Schoenberg and Stravinsky. Here, the repetition may very well represent the loyalty of the strings to the piano leader – regardless of unexpected outcomes. With its entrancing opening, there is an overarching feeling of ‘subconscious’ control in “Prelude to a Feud” that prepares the listener for the entirety of the album.

Advantage Points

The human need for self-fulfillment is readily apparent within a one-on-one sporting competition. If (as Theodor indicates) Advantage Points is overtly a musical metaphor for a tennis match, then covertly, it represents a lifelong and fundamental battle within all of us. From a musical perspective, the physical and emotional sense of a struggle is elicited – a battle for domination that is represented by the alternate application of staccato and legato passages. We are born with an innate, attention-seeking drive to have our fundamental needs fulfilled though competition with others. Initially, the competition is between siblings for the attention of parents, with the goal being to divert attention away from brothers, sisters, and even the other parent and focus it on ourselves. As we grow, boys specifically will begin to compete with their father, which is fundamental for developing a sense of self and a healthy attitude towards others. For the rest of our lives, the battle is between self-fulfillment and limitations set by society and cultures that prevent us from diving into pure indulgence. Based on these theories, it stands to reason that the deeper struggle within Advantage Points is not between two tennis players, but the lifelong struggles we face to satisfy our base impulses – be it defining ourselves from our siblings and parents, boys battling their fathers, or the struggle between societal norms and our need for self-actualization.

Sweet Burden

Many people have pointed out inconsistencies or contradictions in my theories (and actions), but if they took the opportunity to delve into the nuances of what the theories set about to explain, they would not find contradiction all, but rather enlightenment. It was with this mindset that I listened to the seemingly contradictory Sweet Burden. We face many burdens within our conscience and conscienceless, and by their very definition, burdens, on the surface, tend not to be sweet. On listening to the composition, the combination of melancholy viola and somewhat more optimistic piano interact with the delicate interplay required to support contradictory thoughts. Follow a train of thought too long about one or another, and the entire benefit of supporting contradictory thoughts disappears, since one will ultimately win over another. Like the title, the piano and viola do not aim to cancel each other out, but rather persist side-by-side to strengthen each other. Normally, our logical minds would not permit such a contradiction, but within our dreams, it seems perfectly reasonable to have seemingly contradictory thoughts co-exist. Beneficial contradictions held within our subconscious minds are held back by our conscious mind, and this barrier is only broken when we dream. Mr. Gonzales’ aim appears to be set on removing the barrier between logical and illogical thoughts, thus exposing us to the pure and satisfying contradictions of dreams and emotions.

Green’s Leaves

One of my theories states that detachment underlies the repression of ideas. There is a barrier between perceived and stored experience, and corresponding subconscious ideas that are attempting to make their way to our conscious mind. Repression is the mechanism by which we can detach our conscious experience from our subconscious ideas. Green’s Leaves starts off detached, with staccato notes that imply an effort to disconnect or repress reality. Interspersed among the staccato passages are legato passages, with an eventual return to the overall staccato rhythm. The combination of connecting and disconnecting from reality implies an alternation between repression and freedom of ideas and emotions, as may be found in adolescents when they test detachment from parents and other figures of authority in order to define their own persona. Certain mind-altering compounds such as the now-restricted ancient cannabis have also been known to induce a state of detachment. It’s possible that the title of the composition is even a nod to cannabis’ sought-after leaves. The composition’s recognition that we seek out detachment and repression aligns well with my corresponding theories.

Freudian Slippers

We arrive at my favorite composition – a sublime and subtle nod to my fehlleistungen, encapsulated within a another nod to my penchant for wearing slippers during my sessions. Nevertheless, enough of the overt wordplay, for the themes contained within the music that speak to subjects close to my personal failings. While small misspoken words can (and should) be analyzed for underlying meaning and impulse interpretation, the overall theme strikes me as a journey of one of my closest patients – from denial, addictions, and self-doubt, to a healthier, more positive outlook on life, freed from the mental chains that hold one back. The soft and subtle opening piano notes continue a descent that began long before the composition commences. The addition of what I perceive as ‘sad’ strings only adds to the image of abject hopelessness. Not long after the ‘bottom’ is reached, the instruments begin to pick up somewhat – seeing hope on a distant horizon, which is far more desirable than continuing to stare into a dark void. Optimism continue to grow, until a therapeutic breakthrough occurs, which enables the patient to grow and thrive. Not many of you may have guessed that I see myself as the patient within the composition. It’s a sad reality that I abused cocaine for a number of years and was beginning to lose control to the drug until my dear wife and friends intervened and in effect saved my life. To this day, I must admit that the lure of cocaine is great, but I have seen firsthand the damage it can inflict on a person and loved ones. I don’t know if Mr. Gonzales had someone such as me directly in mind while composing, but I thank him for the positive affirmation. More generally, the theme of intervention and redemption is applicable to many situations – not only chemical dependencies. I still listen to this track regularly and am discovering more detail and associations with each play.

Solitaire

Most healthy individuals exhibit an occasional desire for solitude, but for entertainers, the issue becomes somewhat of a contradiction. The balance between attracting fans and simultaneously repelling them typifies the relationship entertainers have with their audience. Although Mr. Gonzales may have been physically alone while recording Solitaire, on a more fundamental level, he knew that his song existed to be heard by others. The entertainer who records their performance is divided solely by space and time with the countless people who will eventually hear the reproduction. It would appear that by definition, an entertainer can never be truly alone, for if they were, they would cease to be considered an entertainer. Musically, from the 1st three Beethoven-inspired notes, the composition is a lively and pleasant exploration, somewhat contrasting with the songs heard up to this point in its absence of chamber instruments. Some of my peers (Bleuler and more recently, Kretschmber) have postulated that an extreme preclusion to a solitary lifestyle encompasses a disorder termed ‘schizoid’, which is obviously not at play here, but does raise questions such as, “Is it the artist, or the piano that longs to be solitary?” Perhaps it’s a combination of both.

Odessa

Odessa is certainly the jewel of Ukraine, but my personal connection to the city may not be widely known. Although my mother was born in Brody, Ukraine, she grew up in Odessa – a city she spoke very highly of, and my cousin Simon recently settled there. Perhaps my most famous connection to the city is through Sergei Pankejeff, a patient of mine from Odessa whom I have called “The Wolf Man”. The key to treating the “Wolf Man” was interpretation, which gave substance and meaning to his seemingly random thoughts and dreams. For Mr. Gonzales’ composition, the Russian elements are unmistakable, as are the occasional forays into descending motives. Overall, there are seemingly contradictory feelings of hope and sadness within Odessa, but as in “Sweet Burden”, contradictory feelings often work well together to expose a greater truth. I can only speculate as to what the greater truth is in Odessa, but I have the distinct sensation that someone who grew up in Odessa was forced to leave, and the melancholy mixed with happiness reflects these warm memories.

Sample This

It’s no secret that I love art – especially antiquities. Perhaps this stems from my assertion that the genesis of curiosity can be found in the childhood riddle of the Sphinx; “Where do babies come from?” More recently, I have been called, “the patron saint” of surrealist art, which I am certainly puzzled by, as I am not a ‘traditional’ artist by any means. Still, I have had the recent pleasure of meeting a certain Mr. Dali, who is an ardent supporter of my theories, and a well-known painter. But what does this all have to do with Mr. Gonzales’ Sample This? On listening to the composition, it struck me that I was being taken on a journey of sorts – one which delves into the unconscious as inspiration; one in which we can gain a sense of self-awareness though a deeper understanding of our “hidden mind”. By understanding our unconscious, we fully appreciate what it means to exist, which frees ourselves from the confines of our conscious mind. This is, I think, what surrealists were moving towards when they ‘freed’ art from the conscious mind, and what I believe Mr. Gonzales is moving towards on his musical journey. The repeated motives, powerful strings, and gentle piano all combine to evoke imagery akin to a surrealistic painting. The surrealists have pointed out that my love for art is what made me a better scientist. I have the same feeling with this composition; there’s a definitive combination of art and science which strengthen each other and allow listeners to reach a higher appreciation for both.

The Difference

I do not believe that for most people, the conflict between id and superego manifests itself in a never-ending war. Rather, the unconscious conflict is (for the most part) ongoing, far more subtle and filled with memories, wishes, and feelings just below the surface of consciousness. Is it with this sense of subtlety than Mr. Gonzales’ The Difference gently explores the relationship between denial and wish fulfillment with dynamics that oscillate between gentle and strict. The wishful portion of our brains longs for an ideal world that exists only within our thoughts, while denial mechanisms force us to see the world as it really is. If this relationship is unbalanced, then we can end up within a fantasy world. I have long believed that emotions are an intrinsic part of our make-up – from both a mind and brain perspective, they are essential to our thoughts. The Difference delves into the difficult question of what guides and shapes our minds, thoughts, and emotions.

Cello Gonzales

As I mentioned in the introduction, I’ve never delved too deeply into music, but my efforts to avoid music may have caused me to miss certain important facets of neurological function. While listening to Cello Gonzales, the first notion that struck me was a gentle back-and-forth rhythm that underscores the composition, and evokes childhood memories of being gently swayed in a parent’s comforting embrace. I have read portions of Kepler’s “Harmonices Mundi”, in which he claims that rhythm and music form the basis of the entire universe, and have often wondered if our own minds have a natural rhythm that governs brain activity. Regardless, the combination of motion and the warm and comforting tonalities of the cello combine to give rise to thoughts and desires established in infancy, but longed for throughout our lifetime. Mr. Gonzales’ musical encapsulation of childhood innocence and protection touches on core facets of how the evolutionary brain operates.

Switchcraft

Transference (or Übertragung in my language), has long been a key component of my therapeutic methods. Early on, I realized that the ability for patients to redirect their feelings to me is paramount to their successful treatment. The transfer can be elicited in any number of ways: anger, parental figure, lack of trust, and potentially a figure of salvation. By analyzing the transference (be it hostile or affectionate), the core issues for the patient can be elicited and ultimately resolved. Switchcraft raises notions of transference through the use of what I consider fantastical or far-reaching timbers and motives, assisted by the emotion inherent in the French horn and flute. Transference is bi-directional (Gegenübertragung or countertransfernce) in that a therapist can transfer feelings to the patient. I have found myself seeing patients through different “eyes” on many occasions; it’s a human trait, and one which I believe poses an issue to therapy. For Mr. Gonzales’ composition, I do not have the feeling of countertransference – only the fantastical notion of a one-way transfer. I believe transference is therapeutic outside of a clinical setting, as is evidenced by the sheer number of people fantasizing that they are someone else, or that key figures in their lives symbolically represent someone else.

Myth Me

We have reached the last song on this wonderful journey, the curiously named Myth Me. I have often wondered how my theories and the person who I am will be viewed years after my death – the entire notion of being turned into a mythical figure is certainly intriguing to me personally. From a psychological perspective, my student Carl and I believe that myths are simply an expression of needs rooted deep within our psyche. These needs underscore our fundamental and universal desire to have figures – heroic and tragic – to reinforce our common beliefs and bring additional meaning to our day-to-day lives. Mr. Gonzales’ composition – the only one in which he sings – predicts (possibly in a self-fulfilling prophetical manner) that “you’re gonna myth me”. The lyrics makes Mr. Gonzales appear to be a tragic figure – someone who never quite reached their ultimate potential and is “mythified” by virtue of how close he came to reaching his goal. By overtly stating (or singing, in this case) his innermost fear of failure, he in fact is admitting his doubt, which gives him the ability to ultimately conquer it. The notion of being a tragic mythical figure is not appealing to myself, or likely anyone else, other than representing a warning to others (as the tragic myths tend to do). Myth Me strikes me as being very therapeutic, and it would serve many of my patients well to imagine how they would like people to remember them, and make positive changes to shape this view.

Conclusion

My rejection of the “illusion” of emotion through music may have been overly harsh, and likely due to personal issues that I have with music in general (but that is the subject of another essay). Mr. Gonzales’ compositions are approachable, humanistic and contain a wealth of accessible emotion. The fact that impressionistic artists and musicians have found inspiration for their artform within my theories leads me to believe that I on a subconscious level, I understood and appreciated the visual and auditory aspects of my theories. In the same way that myths must appeal to the universality of the human psyche, so must art have an approachability. Mr. Gonzales’ compositions are truly approachable, which increases their ability to expose many more people to the beauty of music. I thank Mr. Gonzales for his music, and Thedor for persevering and introducing me to “Chambers”.