Very rarely are we treated to a nexus of talent that echoes the great duos: Bacharach and David, Webber and Rice, Morrissey and Marr, to name a few. The inability for critics and music services to “pigeonhole” Room 29 is ample evidence of the novel space the album holds; not to say the record companies haven’t tried, with made-up categories such as “Classical Crossover.” After repeated listenings, Room 29 solidly remains in a category unto itself – a musical and lyrical adventure. Feist pointed out that Room 29 (the album) is actually the soundtrack to Room 29 (the performance), but while the majority of us miss out on the added visceral benefits of a live performance, Room 29 (the album) evokes powerful mental images of our own creation – a unique and personalized Room 29 performance for each listener. The review below is obviously based on our own experience (save a few choice quotes) and our familiarity with the unbelievably high water mark Gonzales sets for himself.

Very rarely are we treated to a nexus of talent that echoes the great duos: Bacharach and David, Webber and Rice, Morrissey and Marr, to name a few. The inability for critics and music services to “pigeonhole” Room 29 is ample evidence of the novel space the album holds; not to say the record companies haven’t tried, with made-up categories such as “Classical Crossover.” After repeated listenings, Room 29 solidly remains in a category unto itself – a musical and lyrical adventure. Feist pointed out that Room 29 (the album) is actually the soundtrack to Room 29 (the performance), but while the majority of us miss out on the added visceral benefits of a live performance, Room 29 (the album) evokes powerful mental images of our own creation – a unique and personalized Room 29 performance for each listener. The review below is obviously based on our own experience (save a few choice quotes) and our familiarity with the unbelievably high water mark Gonzales sets for himself.

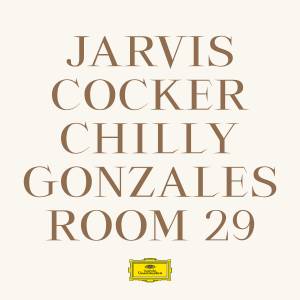

Even before hearing a single note, we only have to look as far as the cover (designed in consultation with the great Peter Saville) to witness the special place this album holds. Gonzales and Mr. Cocker (Jarvis) are proud of being the first Deutsche Grammophon release to feature the parental warning label, as Jarvis explained to the BBC:

We’re very proud, aren’t we, because we’re the very first ever album to be released on the Deutsche Grammophon label that’s got a parental advisory sticker on it. So, the combination of that very famous yellow cartouche and the black and white “beware parents” what your children may be listening to – that a good combination for us.

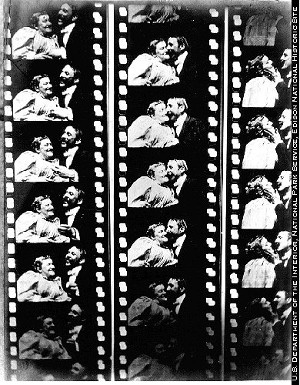

The warning label appears to be another step on Gonzales’ musical revolution – to bring pop sensibilities to classical and jazz music – a very difficult balancing act. The overall album design is classic 1930s, with a beautiful custom-designed font sporting many angular serifs, which exude an attention to the last detail, and capital letters commanding marquee-like attention (plus it’s still clearly legible when shrunk on a tiny phone display). The spacing is such that they words appear as a cohesive group, yet we easily mentally group the words into their individual elements. Warm tones of brown and beige reflect the warmth and comfort a hotel would want to convey – very inviting. Within the liner notes, we find a tasteful scattering of pictures, including one presumably of the actual Room 29 door plaque. The font used within the liner notes closely mimics the font of the number “29″ on the door – classic and easily readable. The liner notes are rounded off with lyrics, tidbits and explanations for many of the songs, plus a list of suggested further reading – if one is so inclined. To us, it’s definitely worthwhile to pick up a physical copy to add to the visceral experience. With the continued decline of album art, it’s always refreshing to see a cover and liner with attention to detail. The first image in the booklet is similar to the one below; the two masters happy in the moment.

The warning label appears to be another step on Gonzales’ musical revolution – to bring pop sensibilities to classical and jazz music – a very difficult balancing act. The overall album design is classic 1930s, with a beautiful custom-designed font sporting many angular serifs, which exude an attention to the last detail, and capital letters commanding marquee-like attention (plus it’s still clearly legible when shrunk on a tiny phone display). The spacing is such that they words appear as a cohesive group, yet we easily mentally group the words into their individual elements. Warm tones of brown and beige reflect the warmth and comfort a hotel would want to convey – very inviting. Within the liner notes, we find a tasteful scattering of pictures, including one presumably of the actual Room 29 door plaque. The font used within the liner notes closely mimics the font of the number “29″ on the door – classic and easily readable. The liner notes are rounded off with lyrics, tidbits and explanations for many of the songs, plus a list of suggested further reading – if one is so inclined. To us, it’s definitely worthwhile to pick up a physical copy to add to the visceral experience. With the continued decline of album art, it’s always refreshing to see a cover and liner with attention to detail. The first image in the booklet is similar to the one below; the two masters happy in the moment.

Oh, we also noticed from the photograph above that Gonzales has a button on his cardigan; you may just be able to see it, so we ‘zoomed’ in to find out what ‘musical spirits’ were at play during recording. It turns out to be a photo of a relatively young Brahms – one of Gonzales’ favourite composers, and sworn Wagner ‘shitdisturber’. Brahms’ spirit definitely made its way into Room 29.

Oh, we also noticed from the photograph above that Gonzales has a button on his cardigan; you may just be able to see it, so we ‘zoomed’ in to find out what ‘musical spirits’ were at play during recording. It turns out to be a photo of a relatively young Brahms – one of Gonzales’ favourite composers, and sworn Wagner ‘shitdisturber’. Brahms’ spirit definitely made its way into Room 29.

People in a Hotel

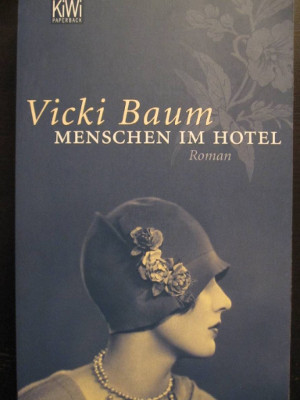

For Vicki Baum’s novel “Menschen im Hotel” (or “People in a Hotel”), the hotel appears to tell the story of the guests – as if the hotel itself is providing the narration, and thusly becomes a constant throughout the novel. Regardless of which guests the story is concentrating on, the hotel ties the novel’s ‘action’ together within a common thread. Whereas scenes in the novel are set against each other similar to doors in a hotel, Room 29′s common thread emanates from a piano, where the scenes are more aptly juxtaposed as neighbouring keys on a piano. Gonzales has explored the concept of “reductio ad absurdum” on songs such as “One Note at a Time”, and even “Never Stop”, where patterns of single notes, or even a single key, are explored, which leads to novel and wondrous results. In Gonzales’ capable hands, each key seems to have a story to tell.

For Vicki Baum’s novel “Menschen im Hotel” (or “People in a Hotel”), the hotel appears to tell the story of the guests – as if the hotel itself is providing the narration, and thusly becomes a constant throughout the novel. Regardless of which guests the story is concentrating on, the hotel ties the novel’s ‘action’ together within a common thread. Whereas scenes in the novel are set against each other similar to doors in a hotel, Room 29′s common thread emanates from a piano, where the scenes are more aptly juxtaposed as neighbouring keys on a piano. Gonzales has explored the concept of “reductio ad absurdum” on songs such as “One Note at a Time”, and even “Never Stop”, where patterns of single notes, or even a single key, are explored, which leads to novel and wondrous results. In Gonzales’ capable hands, each key seems to have a story to tell.

Regarding “Menschen im Hotel”, Baum herself admitted that events within the hotel were merely “moments captured in time”; she wanted the hotel to symbolize life at single point. The fortunes of the people behind the doors may be moving up or down – it’s difficult to say from a single frame of reference. Gonzales and Jarvis “catch a moment in time” for the each of the hotel’s famous guests, with a greater theme taking shape over the course of the album. When each of the stories are played out on their individual notes, a melody appears: Room 29′s tune is playful, but ultimately melancholy. It runs the gamut of human emotions – humour (of course), desperation, regret, hope, and resignation.

In our pre-release write-up, we explored the “bigger” concepts that seemed to stem from the five years of on-and-off collaboration between these masters of composition. We also took a guess at the some of the songs prior to hearing them – some were close, and some were way off. After letting the songs sink into our psyche, we visit and re-visit each track.

Room 29

Gonzales’ melody starts off the album in a wonderfully simplified style, and yet to our ears, the melody communicates a highly-compressed story of the entire album in just the first 14 seconds. Straight away, the melody evokes images of a doorbell chime – a fixed sequence limited by solenoids and metal bars in a doorbell mechanism. Then, the melody moves up – three consecutive notes signal a climb to a higher level – growth, knowledge – an adventure. Then, for the next two sequences, only two notes are struck in consecutively, with the last note in each sequence lingering, which leaves space for contemplation. The very last note of the sequence is back where we started – we went on a journey, learned new things and returned home.

The melody is also reminiscent of the Westminster Quarters (the chimes used for Big Ben), possibly signalling the proverbial “for whom the bell tolls” question. Gonzales’ skill and experience can move a story of hope and adventure into melancholy. Doorbells and clock chimes mark events – visitors and the passing of time, and Westminster Quarters ends on either the dominant or tonic for a happy, satisfied ending, whereas Gonzales’ melody is somehow less optimistic.

During Gonzales’ concerts, he’ll often have a “recapitulation” of the entire concert at some point (“for the benefit of people who came late”, he explains). In the span of a minute, the entire concert to that point is played back at breakneck speed; a memorable and humourous effect. He is a master of audio compression, but not in the sonic MP3 sense, but rather in reducing emotions and stories to as few notes as required. From the melody, we expect Room 29 (the album) to contain laughter, growth, regret, loss, and a warning for us to heed, lest we follow the same fate as the inhabitants of Room 29. 10 notes, 14 seconds.

Although the melody feels sad, Gonzales then adds his sourdine left-hand chords to move from stark and barren to warm and somewhat melancholy. Further on, Gonzales explores the upper registers with a wandering melody of sorts that compliments Mr. Cocker’s “gravelly sonority” (as Gonzales put it). Halfway through the song, the melody is expressed within chords; telling not just one tale, but the story of multiple people, interconnected by their stay in a hotel room with a piano. In the final quarter of the song, Gonzales ventures to the highest octave, where the short, taut strings vibrate more like bars of metal than strings, and where we have a child-like, dreamy, music box feeling. The last two chords end where the opening melody ended, but at this point, we’re more familiar with where the melody is headed – we expect it, so it sounds complete, but there are still questions to be answered.

All the while, Jarvis’ vocals are miked so closely that we can hear every nuance. His vocalizations seem very personal – as if he’s gently reading a Chateau Marmont brochure into our ear. At one point, he lightly beats his chest – almost as if to ‘force out’ the words “Room 29.” Although we won’t explore the lyrics as closely as we’d like to, one telltale line from the song that, to us, explains a large part of the album is:

Cause no one ever got turned on by the Whole Earth Catalog

The Whole Earth Catalog was a wonderful California-based counterculture publication that ran from 1968 to 1972. Within its pages, one could find tools, tips, and tricks on how to “do it yourself” (DIY) – breaking reliance on large corporations to do the thinking (and work) for you. Steve Jobs was greatly influenced by the magazine, which (surprisingly) contained early reviews of computers and synthesizers (by the great Wendy Carlos, no less). Jobs liked to quote the message on the back cover, “Stay hungry. Stay foolish.”

What Jarvis seemed to be alluding to was the relative ‘unattractiveness’ of DIY culture to the masses. Hollywood, movie stars, glamour, rumours, movies, TV shows are all far more exciting than ordering a pottery wheel. The issue is that ultimately, Hollywood is the sugar of our social diet – we love consuming it, but it quickly leaves us unfulfilled and on a quest for more. Contrast this with the mental satiety one feels when learning and doing things yourself. In the case of the latter, Gonzales advocates for hands-on piano – regardless of skill level and age. His books and concerts underscore the notion that you don’t have to be a passive listener; you can create or play music that is special to you, which is very satisfying.

Reviews to-date have happily avoided any comparisons to the Eagles’ “Hotel California” – with good reason, but we’re not afraid to venture into “Eagles” territory. For us, the connection to “Hotel California” (a concept album itself) is unavoidable and deserves exploration. Gonzales has played “Hotel California” on and off in concert since 2010, and more than likely learned to play it as a teenager. In a recent concert, he compared the song to “cocaine” for your brain – it’s too catchy to even risk playing in full, else you’ll be hooked. It’s long been thought that the Eagles wrote the song with the Chateau Marmont in mind, despite the cover image of the Beverly Hills hotel. The narrator within Hotel California appears to be warning others to avoid the same mistakes he’s made, which ultimately ‘trap’ him within the confines of the hotel. In a sense, the song symbolizes California, but also serves as a larger metaphor for America as a whole. The Eagles warning was to not eschew personal responsibility for the negative impact the pursuit of wealth and power can have on people, society, and the environment. The Eagle’s message was delivered in such a catchy and memorable “package” that people may have missed the message entirely. Jarvis makes it far more straightforward – be aware of what you are feeding your brain: entertainment has always, and will always win.

Room 29 is perfect as an album opener – like a great first chapter in a book, or (more appropriately) the first 10 minutes of a great movie.

Marmont Overture

Gonzales’ subtly rolled chords gently move us from the stark melody of Room 29, into a warm and inviting place. A single struck key seems to represent the service desk bell – demanding our attention and commanding a call to action. As we mentioned in our first review, the overture sets the ‘mood’ for a film, and here, we can imagine being in awe of the hotel – moving off the street and through the doors into another world. The sound effect of a busy lobby is overlaid onto the piano as we move through the halls passing strangers on the way, and into an old elevator. Finally at our destination, there’s anticipation and excitement – through tremolo and repeatedly struck keys. Lugging our suitcase down the final stretch, we fumble for our door key and finally pass through the threshold. It’s a bit of “virtual reality” through music and definitely frames the rest of the album, which starts immediately.

Tearjerker

We’ll stand by our previous look at Tearjerker, but it’s interesting to note how quickly the words You are such a jerk appear after the overture – almost a slap in the face as you open the door. The sequencing of the album has obviously been very carefully thought out.

Musically, Tearjerker stands out as one of the deep and emotional tracks off the album. Ryuichi Sakamoto was definitely influenced by Debussy, Ravel, and Satie – composers who Gonzales has often been compared to, so it’s no surprise that Gonzales’ composition shares some “DNA” with a Sakamoto composition (enough so for Gonzales to add a Sakamoto songwriting credit). Sakamoto’s signature style is to play a western harmony supporting an eastern (or Gamelan) melody, with specific dissonant notes. The overall effect is achieved by maintaining odd intervals (7th, 9th, 11th, and 13th) between the notes of the melody and harmony. The resulting richness of the harmonics is deeply emotional and adds a mysterious, ambiguous, and slightly disturbing quality to the compositions.

In Tearjerker, Gonzales may have wanted to convey the feelings the main ‘character’ is having – doubt, regret, & sadness over their current state and their actions. Using an east/west dichotomy, the listener feels calm, but with a sense of uneasiness. Jarvis’ lyrics are a striking portrayal of what must be an all-too-common sentiment in Hollywood. The breakfast is inclusive line is curious; Jarvis may have been portraying the character as shallow and greedy – more concerned about missing a ‘free’ breakfast than the people around him (a hotel-based take on greed, if you will). Lush, poetic, and emotional, Tearjerker is definitely a standout track.

Interlude I – Hotel Stationary

Here, Gonzales takes us through slow, measured movements of a short beautiful story – reminiscent of a Bach Adiago. Halfway through, we hear the scribble of a fountain pen against paper – someone appears to be writing a note on hotel stationary. Shortly thereafter, prolific author and film historian David Thomson’s grainy mid-Atlantic voiceover enters for the first time (of many). He indicates that he can, show you something that happened – once. Gonzales’ piano maintains its upper-register movements, which stop, at which point we hear just the note being written.

This short piece could be an introduction for the next composition, which features Mark Twain’s daughter, or it could be the suicide note of Paul Bern (Jean Harlow’s first husband), or David Thomson writing down the details of yet another Hollywood tale from the Chateau Marmont.

Clara

Set to the tune of Gonzales’ sublime Armellodie (from Solo Piano), Jarvis’ lyrics explore Clara Clemens’ time at the Marmont. As we mentioned in our first look at Room 29, Clara was Mark Twain’s daughter, but she could not live up to the image of her famous father and chose to live in relative anonymity. She married a composer and concert pianist, who passed away at a young age, leaving Clara with their only daughter. Jarvis speculates that it is Clara’s husband’s piano that was left in Room 29 – a great theory, since the piano could tie together elements of talent, dedication, money, fame, loss, and many other concepts explored in Room 29.

Armellodie is a lush and gorgeous song; likely apt to pique the curiosity of Jarvis Cocker fans, who should definitely pick up Gonzales’ Solo Piano for the original version, or Chambers, if they prefer the version featuring the Kaiser Quartett.

Bombshell

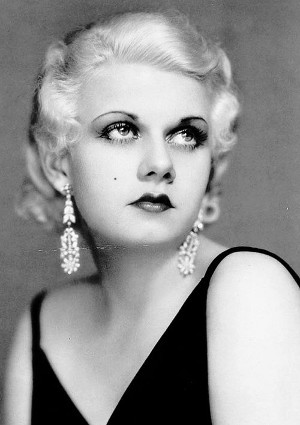

One of the most curious tracks off Room 29 starts with an incessant ‘drip’ of water and quickly moves to what one could describe as a ‘countdown’ cadence – as if a timer has been set on a clock (courtesy of an unwavering pizzicato note, and metronomic piano sequence). David Thomson introduces us to Jean Harlow, …she marries this man Paul Bern, and… at which point Jarvis takes over the vocals. A lilting piano motif is repeated as it moves up and down the octaves, along with Jarvis’ singing. For this composition, the Kaiser Quartett joins in to add elements of suspense, exclamation marks, and the additional emotional power that comes from a string quartet. Halfway through, Gonzales’ piano breaks into a lilting (and familiar) melody that climbs up the octaves, eventually merging with the legato strings already in motion. A ‘distant’ Jarvis voice (almost out of body) sings, I can feel you slipping away.

One of the most curious tracks off Room 29 starts with an incessant ‘drip’ of water and quickly moves to what one could describe as a ‘countdown’ cadence – as if a timer has been set on a clock (courtesy of an unwavering pizzicato note, and metronomic piano sequence). David Thomson introduces us to Jean Harlow, …she marries this man Paul Bern, and… at which point Jarvis takes over the vocals. A lilting piano motif is repeated as it moves up and down the octaves, along with Jarvis’ singing. For this composition, the Kaiser Quartett joins in to add elements of suspense, exclamation marks, and the additional emotional power that comes from a string quartet. Halfway through, Gonzales’ piano breaks into a lilting (and familiar) melody that climbs up the octaves, eventually merging with the legato strings already in motion. A ‘distant’ Jarvis voice (almost out of body) sings, I can feel you slipping away.

About two-thirds through the song, Jarvis’ voice fades, and Gonzales strikes a single note in a pensive manner, morphing into a dreamlike sequence – replete with shimmering vibraphone. Eventually, the note is joined by discord and ‘falls’ down the scale, ending the song on a single struck vibraphone note.

To make sense of Bombshell, let’s look at some of the backstory behind the composition. As Jarvis explained to the BBC:

Well, the thing with Jean Harlow’s honeymoon was that actually happened in that particular room. So Jean Harlow was a massive movie star – the biggest kind of sex symbol of the early 30s, and she had her honeymoon in Room 29 of the Chateau Marmont. But it was a sad story, because the guy she married, Paul Bern, for some reason (people don’t know exactly why) he was unable to consummate the marriage and he actually committed suicide about a month later. So, there was something about that, because what the album is about, as well as being about the hotel, it’s also about its links with the film industry – this seemed the perfect story that you have this woman who on the screen is desired by most of mankind, but in her own life, the guy she marries can’t deal with this discrepancy between the thing he sees on the screen and the actual woman that he’s married to.

The “Bombshell” in this case appears to refer to the term used to describe the incredibly gorgeous and voluptuous ladies of the silver screen, but also to the casing of a bomb set to explode. It’s hard to hold a bombshell, may be apt to describe what would happen if people were confronted with their ‘fantasy’. For Paul Bern (presumably the song’s narrator), the bomb eventually exploded with tragic results.

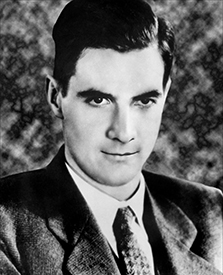

Interestingly, the 1932 award-winning movie “Grand Hotel” was based on “Menschen im Hotel”, and (to close the circle) is connected to Room 29 by way of Paul Bern. He co-produced “Grand Hotel” with Irving Thalberg, but Paul would commit suicide (under what many still believe are mysterious circumstances) only six days before the film was scheduled to premiere.

Belle Boy

With the swift “ding” of a desk bell, we’re called to action in “Belle Boy” – a hilarious adventure through the eyes of a bellboy, but with an added twist. The piano cadence is very percussive and appears to be preparing for a rapper to appear. Jarvis’ character chimes in with health drink ingredients, urgently required by one of the hotel guests. The Andersons cannot wait a moment longer - may be homage to Wes and his own love of hotel stories (The Grand Budapest Hotel). All the while the piano cadence continues, unwavering, with the occasional piano ‘hit’. The Kaiser Quartett adds détaché strings, which adds an element of suspense and urgency. At one point, the cello player (Martin) knocks the belly of his instrument for an effective “door knock” effect.

Meyer Harris Cohen, otherwise known as Mickey Cohen was a notorious gangster on the sunset strip who was known for his equisite style (he reportedly owned over 200 tailor-made suits). Mickey Cohen loved style so much that he opened a store called “Michael’s Exclusive Haberdashery” on the sunset strip. As far as his stay at the Chateau Marmont was concerned, he moved into Room 29 (known then as the Jean Harlow suite), and at one point was discovered “having relations” with a lady. Mickey just kept on as if no one was there, much to the horror of the bystander; for the benefit of the bellboy, as Jarvis describes.

Meyer Harris Cohen, otherwise known as Mickey Cohen was a notorious gangster on the sunset strip who was known for his equisite style (he reportedly owned over 200 tailor-made suits). Mickey Cohen loved style so much that he opened a store called “Michael’s Exclusive Haberdashery” on the sunset strip. As far as his stay at the Chateau Marmont was concerned, he moved into Room 29 (known then as the Jean Harlow suite), and at one point was discovered “having relations” with a lady. Mickey just kept on as if no one was there, much to the horror of the bystander; for the benefit of the bellboy, as Jarvis describes.

Just past the halfway point of the song, the melody changes to lighthearted (almost a miniature piece within the song) – in sharp contrast to the driving rhythm of the song up to this point. The bellboy appears to be daydreaming and fantasizing about a different life with “butterfly steak and baby peas” (a favourite of Howard Hughes) as a triangle incessantly chimes in the background. Gonzales’ melody here is addictive and effective at conveying a ‘fantasy’ theme, which eventually decays back into the original cadence, but with a repeatedly struck, somewhat ominous bell. For the final few bars, the strings and piano are all in sync with the ominous staccato rhythm escalating tension and urgency.

The song’s theme may be underscoring the dreams of hopeful Hollywood stars, who have to take odd jobs between acting gigs to make ends meet. We certainly know that Los Angeles has its share of ‘undiscovered’ talent waiting on tables or ensuring people’s hotel stay is enjoyable. Backing up, the song may also be alluding to servitude and our place in life – some of which we have control over and some of which we don’t. We’re all “bellboys” in a Dylanesque sense, and have to answer a call to someone – be it the general public, adoring fans, managers, relatives, and so on. How well we perform obviously impacts others, but also determines the course of our own lives.

Howard Hughes Under the Microscope

Gonzales starts of this ‘instrumental’ track with a softly struck low A-flat, which decays while the gentle melody is introduced (the A-flat makes an appearance throughout the song). David Thomson’s voiceover re-appears and tells us a bit about Howard Hughes. Gonzales’ composition seems to juxtapose what we’re hearing about Hughes – and we’re left with the impression that we should somehow feel sorry for Mr. Hughes in a “poor little rich boy” sense. A male chorus joins in with “aah-a-aah-a-ah” – almost a Gregorian or funeral chant. At the end of the song, David indicates, …and he dies alone. Howard Hughes did descend into a state of madness during the last years of his life, likely fueled in part by his dependence on drugs to manage pain from a test plane crash. As Roger Ebert wrote, “What a sad man. What brief glory.”

Gonzales starts of this ‘instrumental’ track with a softly struck low A-flat, which decays while the gentle melody is introduced (the A-flat makes an appearance throughout the song). David Thomson’s voiceover re-appears and tells us a bit about Howard Hughes. Gonzales’ composition seems to juxtapose what we’re hearing about Hughes – and we’re left with the impression that we should somehow feel sorry for Mr. Hughes in a “poor little rich boy” sense. A male chorus joins in with “aah-a-aah-a-ah” – almost a Gregorian or funeral chant. At the end of the song, David indicates, …and he dies alone. Howard Hughes did descend into a state of madness during the last years of his life, likely fueled in part by his dependence on drugs to manage pain from a test plane crash. As Roger Ebert wrote, “What a sad man. What brief glory.”

For his 1930 award-winning independent aviation war film “Hell’s Angels”, Hughes would end up casting a teenage and demure Jean Harlow in the leading role. Hughes did reside at the Marmont (and many other hotels) after his plane crash, but (contrary to rumours) was not present during Jean Harlow’s honeymoon stay. Howard Hughes is a fascinating character; the sad sentiment in the song reflects his tortured and lonely existence, regardless of how many millions he was worth. At the end of the song, Gonzales’ piano gently fades and disappears into obscurity, mimicking the real-life anticlimactic withdrawal from life of Howard Hughes.

Aside: David Thomson

The insightful choice of David Thomson as a narrator of sorts further emphasizes and deepens the historical connection of the Chateau Marmont to Hollywood and our continued fascination with fame and movies. Celebrated author John Banville called him “the greatest living writer on the movies.” Mr. Thomson, besides having great vocal timbre is a prolific author and has supplied memorable quotes through his extensive cinematic knowledge. One of his quotes that Gonzales may agree with is, Art does not need Councils. It needs imaginations.

Salomé

Previously, we examined the Marmont connection to Salome through Billy Wilder and his “Sunset Boulevard” movie starring Clara Bow as a faded silent movie star hoping to resurrect her career through her performance of “Salomé.” Now that we’ve heard the witty and insightful Salomé, we take a slightly different point of view.

Previously, we examined the Marmont connection to Salome through Billy Wilder and his “Sunset Boulevard” movie starring Clara Bow as a faded silent movie star hoping to resurrect her career through her performance of “Salomé.” Now that we’ve heard the witty and insightful Salomé, we take a slightly different point of view.

Starting with the twirl of a tambourine (which features throughout the song), Gonzales’ sourdine piano melody gently follows Jarvis’ softly spoken lyrics. The melody and words both belie the content of the song – a gentle and beautiful melody underscoring the mental image of Salomé carrying Jarvis’ head around in a box – and Jarvis is witnessing (and even enjoying) the event from a third-party point of view. Eventually, the Kaiser Quartett join in to soar and reinforce the mental imagery, with a violin taking over the main melody, relegating Gonazles’ piano to a temporary supporting role. The overarching theme of Salomé equates the temptress with Hollywood, and the exploited ‘head in the box’ is likely akin to an actor watching someone else profit from their televised image.

One can also draw parallels between Jarvis’ version of Salomé, and Nikolai Gogol’s “The Nose”, which Gonzales and his brother wrote a musical for while in school. In “The Nose”, the main character wakes up to discover that his nose is missing and has assumed a life of its own – eventually surpassing and becoming more successful than its original owner. In Salomé, Jarvis’ character witnesses his head in a box that is garnering rave reviews; the viewing figures just when through the roof. All the while, Jarvis’ character is simultaneously enjoying the sight of Salomé dancing and wishing that the dream that started in his heart would come to an end. “The Nose” and Salomé seem to use a sense of humour and satire to poke fun of people who are far too superficial and will do anything to climb the social (or Hollywood) ladder.

Interlude 2 – 5 hours a day

We were a bit ‘off’ on thinking that the title of this song referred to 2-5 hours a day of practice; it should have been read as “Interlude 2″ – “5 hours a day”, and refers to the average amount of time children spend watching television (when television was popular).

The lonely flute is somewhat reminiscent of “Hinterland Who’s Who” – a series of short nature films produced by the National Film Board of Canada (incidentally where “Boards of Canada” derived their name from), which Gonzales likely would have seen during his youth in Canada (some television programs are educational).

Gonzales joins the flute and French horn with a ‘spattering’ of piano notes – no connected melody as of yet. David Thomson explains where the 5 hours a day came from, and adds, I bet you didn’t spend 5 hours a day talking to your parents, at which point the song progresses into the next track. This short and moving composition appears to be an introduction of sorts for the next song – explaining where Jarvis is coming from.

Daddy, You’re Not Watching Me

Gonzales’ piano opens with the same melody as the flute in the previous track, while Jarvis softly frames a child playing piano – their father obviously not paying attention. Shouldn’t you be guiding me? Already we have the impression that the song isn’t literally about a child playing piano, but rather having to grow up with parents who are too busy and find it easier/better if the children are quietly in front of the television. The piano keys and song may represent life and growing up – the importance of passing down wisdom and our ‘songs’ to the next generation. But generations of children were reared in front of the television, which took the place of parents, and taught children someone else’s life lessons and values.

In the absence of God, I guess you’ll do for me, referring to the magic lure of television as children seek out evidence of a higher power. Gonzales’ piano remains childlike and impressionable throughout, while a female singer in the background calls out her siren song, luring children closer to the screen where they ‘crash’ against the glass. One has the impression that Jarvis has struck at the root of the problem – generations worshiping a television instead of becoming involved with personal growth – passivity as opposed to activity, which harks back to the “Good Earth Catalog” discussion. Fantasies are exciting and easy on the eyes, but may ultimately lead to a self-perpetuating cycle of dependency which benefits relatively few individuals.

The Other Side

In what may be the most industry-aware song on Room 29, Gonzales’ playful, bouncy piano cadence supports Jarvis’ character’s ‘confession’ of sorts – that the ‘other side’ of the screen is not all it’s cracked up to be. A lie, phony, scripted, exclusive – and trust this fellow – he’s been ‘behind the scenes’ and seen all the cables and wires.

For the next verse, Gonzales adds a more harmonically-rich harmony to the cadence, which removes some the playful elements, while Jarvis’ voice is backed up by a baritone, mimicking (almost satanic) voice, explaining that his character had aspirations and dreams from a young age, but reality struck and it wasn’t anything like he dreamed it would be. The character is warning, there is nothing on the other side, while Gonzales simplifies the melody, but increases the ‘desperation’ though keyboard pressure.

Jarvis’ character eventually admits that he’s been playing for the other side – almost a betrayal, if we were using a sports analogy. A football player who purposely throws the game because he’s been ‘bought’ by the other side, or a corporate director that sells company secrets, or a seemingly normal person who is doing the bidding of a corporation to move more product (i.e. acting). There’s a wonderful pause at the end of the song where Jarvis’ voice is laid bare and shaky – unsupported by piano until after he has finished speaking.

The apparent sparseness of “The Other Side” is striking – it causes one to lean in and listen more intently, as the message seems personal, reinforced by the sing-song rhythm of Gonzales piano. Gonzales knows the power of leaving room for people to think and messages to sink in, and Jarvis takes up the challenge of carrying the vulnerable vocals – a very effective combination.

The Tearjerker Returns

The Kaiser Quartett starts off by replacing the role of Jarvis’ voice in the song; the strings express the sadness and regret that Jarvis communicated. Gonzales’ solo piano takes over the main melodic role to an even greater effect than the original track. There are no words to communicate – just pure musical sentiment, and it’s very emotional. The placement of “The Tearjerker Returns” may be to open us up emotionally to the next song – the longest on the album.

A Trick of the Light

A piano theme in reverse starts off “A Trick of the Light”, which often signifies a desire to go back in history with newfound clarity; “If I only knew then what I know now – I would have made different choices.” After Gonzales and Jarvis tell us the stories of Room 29′s famous former inhabitants: sadness, disappointment, and where Hollywood all began from the “eyes” of the piano, Former Room 29 residents feel somewhat ‘tricked’ and manipulated and seek redemption (and possibly forgiveness).

A piano theme in reverse starts off “A Trick of the Light”, which often signifies a desire to go back in history with newfound clarity; “If I only knew then what I know now – I would have made different choices.” After Gonzales and Jarvis tell us the stories of Room 29′s famous former inhabitants: sadness, disappointment, and where Hollywood all began from the “eyes” of the piano, Former Room 29 residents feel somewhat ‘tricked’ and manipulated and seek redemption (and possibly forgiveness).

There’s no eschewing personal responsibility, but there’s something more deviant at play – something that seeks to take advantage of our very nature and core as human beings. Much like food companies seek to continually exploit our inherent desire for certain food tastes and textures (under the guise of ‘pleasure’), Hollywood seeks our attention and partakes in a never-ending cycle of glitz, glamour, rumour, and being part of the ‘in’ crowd to run the ‘machine’, with little regard for the effect it has on people (actors, audience) and society in general.

Somewhat ironically, Gonzales’ thematic selection of music is rooted in Gato Barbieri’s soaring title track suite from the controversial “Last Tango in Paris” – a 1970s string-heavy composition that evokes images of mystery, wonder, and magic in the city of romance, while avoiding ‘cliche’ Parisian music. Gonzales and Jarvis lived for many years in Paris; their choice of Gato Barbieri’s theme may stem from personal experience with the City.

After the backwards introduction, Gonzales settles into a back-and-forth waltz, which has certain hypnotic elements as one imagines a pocket watch swinging back-and-forth. As the thematic music continues and builds, Jarvis’ character appears to view Hollywood with newfound clarity as simply people in a hotel room: Ben Hur? Just a guy at the minibar. Cleopatra? Just a lady taking a shower. Astronauts on the moon? Just actors on a Hollywood sound stage – a trick of the light. Life with the boring bits edited out, may allude to our human need for escapism and fantasy, almost as if our brains have to imagine a better future in order to survive the daily reality we’re faced with.

Gonzales’ piano starts to reach higher and higher octaves in a steady climb, but not quite reaching the really high points yet. By the time Jarvis recalls all the fantastical stories he’s seen, Gonzales moves to a staccato rhythm, almost reading out a laundry list of past film plots. As the character reaches out to touch the screen, Gonzales’ piano crescendos to add to the excitement Jarvis is portraying, but the melody and lyrics are both brought back down as the character admits, well, I wasted my life. You can almost see a finger wagging at the screen to say, you tricked me alright; the music fades and all you hear is Gonzales repeatedly striking a single key.

The interplay of lyrics and piano here is incredible – there’s movement and reinforcement, sentiment expressed and underscored on the part of the piano and voice – we’re in awe. The character is almost on his knees – trying to mentally balance what he once thought and the reality he know knows. Gonzales’ gentle chords are sympathetic to his plight. A magic box. Upon which life leaves a stain, – again, brilliant imagery is used here to show how utterly insignificant the character feels – comparing life akin to “stains” (silver colloids) on film as Gonzales plays a quiet melody, only interrupted by the occasional tremolo string appearance.

There is a ‘reveal’; the character is onto the ‘trick’ – windows are for looking through, and Gonzales and his backing symphony wholeheartedly move into “full emotional” mode with soaring piano and strings – the character feels the full weight of his life’s decisions and resigns himself to his fate: I’m waving goodbye to the love of my life, as the music moves back to gentle solo piano with a ‘final’ rolled chord. We’ve come to the end of the first ‘reel’ and we can imagine someone shutting down the projector as the film slows, the light fades, and we can see the dim, individual frames of film before the theater turns dark.

After a moment, the last few seconds of dialogue and music are again played back in reverse, but with a forward-played Gonzales tremolo leading up to ‘dreamy’ rolled chords in the high octaves. We hear a female voice announce, This is the Chateau Marmont message center, as gentle piano and tremolo strings build up to the full emotional power of Gonzales and orchestra – exploring the highs and lows we just experienced before settling back to the repeatedly struck single key and a final flourish.

For us, the pause and answering message hint that the entire experience following our arrival in Room 29 was a dream – one that was ‘fed’ by the spirits in Room 29 and its baby grand piano. The character wakes up with newfound clarity as the spirits told their subconscious tale, but the final few bars of the song indicate that instead of being inspirational, the end result is more of self-awareness, acceptance and resignation.

Martin Scorsese once said that “film itself is a special effect,” and from Room 29 liner notes, the ‘trick’ at play stems from the physical and psychological phenomena that comprise movies themselves. A brilliant exploitation of the notion that movies are a series of still pictures played back in such a way as to ‘trick’ your brain into seeing individual frames as continuous motion. Lyrically, Jarvis conflates ‘real life’ with ‘movies’ asking the somewhat rhetorical question of, “what is real life really, anyway?” If the movies are fake – just a trick – how can we be so drawn into their world? Jarvis’ character appears genuinely angry at the movies for how his life turned out; it’s not like the movies portrayed at all – it was just a trick of the light. He saves the most poignant lines for last: What a surprise: the love of my life was a trick of the light. The line “what a surprise” is delivered in a deadpan manner – a sarcastic recapitulation of what he’s since found out, but now seemingly resigned to life events that transpired.

We definitely view “A Trick of the Light” as a climactic song – daring and adventurous, we haven’t stopped learning from this incredible composition.

Room 29 (Reprise)

We end the ‘main’ feature as we started, with the lovely melody that recounts the tale of our weary traveler. Jarvis softly and happily whistles as the character prepares to leave the hotel. The music fades and we hear the sound of the elevator doors and the busy hum of daily life outside the doors of the Chateau Marmont. Cars honk on Sunset Boulevard, but one car horn has a distinctly ‘old’ feel to it. It honks once, then again from further away as if one of Room 29′s former residents is saying, “so, long – thanks for visiting!” as they drive away in their classic auto.

We end the ‘main’ feature as we started, with the lovely melody that recounts the tale of our weary traveler. Jarvis softly and happily whistles as the character prepares to leave the hotel. The music fades and we hear the sound of the elevator doors and the busy hum of daily life outside the doors of the Chateau Marmont. Cars honk on Sunset Boulevard, but one car horn has a distinctly ‘old’ feel to it. It honks once, then again from further away as if one of Room 29′s former residents is saying, “so, long – thanks for visiting!” as they drive away in their classic auto.

EPILOGUE

Ice Cream as Main Course

As a final ‘treat’, Jarvis seems to channel the spirits of Los Angeles residents, recalling how good times were way back when, and how the current generation of consumers hardly strive to break down any doors and barriers – content that generations before ‘paved the way’ for today. Jarvis’ Sheffeldian roots are almost accentuated and clearly heard through words like “rhoom” (rum).

Musically, Gonzales starts out with soft piano accompanied by plucked bass, but quickly moves to playing ‘big’ chords to support the ‘bar’ mood, while the strings play a lilting melody in the background.

The music and lyrics swell to a crescendo in the last chorus before rapidy dropping off for the final verse, where Jarvis emphasizes and slows on the words “sexual intercourse”, which (as I’ve heard) will have an effect on many women listening to that particular lyric. The song playfully ends with, We’ll order ice cream as main course, which is perfect for this carefree look back at the early days of Hollywood, and may even be a wink to Howard Hughes, who had a particular penchant for ice cream. Humourous and melancholy – a great closer.

Our Epilogue

In our pre-release review of Room 29, we examined California, in part, as a beautiful statue with a ‘twist’. What we didn’t say was that the statue was made possible due to a wealthy patron: Mr. William Blackhouse Astor – heir to the Waldorf-Astoria hotel and property-based fortune. It appears that hotels have played a supporting role in shaping America; special places where (as Jarvis describes), behaviours and experiences (good and bad) are amplified.

Feist has an insightful take on Room 29: it explores the messy solitude that life isn’t as easy as films told us it would be. There’s no velvet rope and red carpet in real-life, but with the proliferation of Hollywood and the apparent ‘closeness’ of social media, the discrepancy Feist describes seems to be worsening. We’re even moving away from the shared experience of a hotel into the relative isolation of AirBnB, which doesn’t seem to have the same classic charm or connectivity with people. The exploration of the subject doesn’t bring us to a neat, packaged conclusion, but rather a greater sense of awareness of what’s important for personal growth, and the realization (or reminder) that there are gifted, hard-working people behind the entertainer facade who aren’t all that different from you and me.

Even after listening to the album many times, tidbits and nuances continue to appear; there are many layers to explore in this classic. Deutsche Grammophon knew they had something special on their hands; the skill, perseverance, and attention to detail of Gonzales and Mr. Cocker have resulted in one of the most unique and compelling albums we’ve heard in a long time.

Brilliant article. Thank you!

Heard this ( a part thereof) at a large audio show in L.A. It study with me.