For most of us, hard work achieves short-term goals that will likely be consumed and seen by a few people — ourselves, co-workers, friends, and so on. Even people whose work is seen by millions of people know that change is relatively constant; web designs that work today will be overrun in a few months, and authors can publish second editions. Imagine you had only one shot to create something to be consumed by millions of people. Not having the luxury of change requires a different mindset and an ability to know what « done » looks like, since the alternative is finding yourself a stuck in cycle of constant change. In a recent interview, Gonzales discussed how committing to a point-in-time version of a song creates a gold standard on which all subsequent performances will be measured against. Interestingly, the more we listened to Solo Piano III, the more the pieces changed and morphed to reveal new insights and mental pathways to explore. The song didn’t have to change for us to see things from a different perspective — the music changed our perspective. This happened with Treppen, and based on our change in viewpoint, we present our second review.

For most of us, hard work achieves short-term goals that will likely be consumed and seen by a few people — ourselves, co-workers, friends, and so on. Even people whose work is seen by millions of people know that change is relatively constant; web designs that work today will be overrun in a few months, and authors can publish second editions. Imagine you had only one shot to create something to be consumed by millions of people. Not having the luxury of change requires a different mindset and an ability to know what « done » looks like, since the alternative is finding yourself a stuck in cycle of constant change. In a recent interview, Gonzales discussed how committing to a point-in-time version of a song creates a gold standard on which all subsequent performances will be measured against. Interestingly, the more we listened to Solo Piano III, the more the pieces changed and morphed to reveal new insights and mental pathways to explore. The song didn’t have to change for us to see things from a different perspective — the music changed our perspective. This happened with Treppen, and based on our change in viewpoint, we present our second review.

Treppen (deuxième étage)

Treppen (which bears a passing resemblance to the English countercultural word Tripping) shows how short the distance is between predictability and a new adventure. Every so often, we feel as if the same day is repeating over and over as we trudge up and down the same steps, exhausted at the end of the day. Gonzales shows us that change doesn’t have to be drastic to be interesting — it only takes one extra step to break our pattern and start to admire the beauty in everyday things around us. When we’re young, predictability is essential for proper growth and development; children revel in watching the same show dozens of times just to see their predictions validated. As we grow older, the novelty wears off and we seek out new experiences and input, but somewhere within us, we also appreciate the role predictability plays.

Despite what big data analysis claims, we don’t have to live life as predictable automata and machines. In Apple’s famous Ridley Scott-directed « 1984″ commercial, the ‘masses’ were portrayed as obedient and identical non-thinking characters. The iconic runner who smashes the screen of conformity with a thrown hammer has parallels to Gonzales’ single additional note. As we listen to Treppen’s opening childhood scale, we feel the comfort of predictability, combined with a longing for something different. When Gonzales throws his 9th note ‘hammer’, our minds perk up and we become curious to see where the melody is headed.

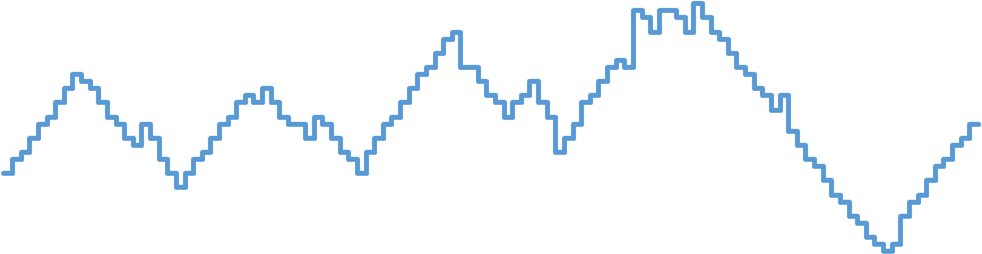

If we look at a graph of sequential note distances in Treppen, the overall ‘step’ structure is apparent, and little surprises become obvious as deviations from the regular pattern. From afar, the pattern resembles a mountain landscape, and our journey isn’t complete – we’re still climbing at the end. Close-up, Treppen appears as a tiny slice of a sampled waveform; an oscillation between low and high, which is the fundamental element of sound. When smoothed, the wave could even have been produced by the strings of a piano, which means that the note « steps » recreate the sound of the instrument they were being played on. This fractal view of the composition lends itself well to natural phenomena; the biochemical molecules and reactions that take place under a microscope are beautiful and feel as if guided by an invisible force — fundamental to life itself. When the view is pulled back to reveal the organism, one realizes that beauty and complexity exist at all levels. Man is certainly stark mad; he cannot make a worm, and yet he will be making gods by dozens, goes a famous quote by the French ‘essayist’ Michel De Montaigne. It’s the same for music, as we can’t explain its powerful draw, and yet we somehow feel more human when we are affected by Gonzales’ compositions.

As a reminder of life’s « ups and downs », Treppen beautifully draws on familiarity and comfort, while simultaneously poking us out of complacency through unexpected deviations. The great composer Schoenberg sought to teach his students what they didn’t know — not what he knew, since he wanted them to search and grow beyond his own ‘limited’ knowledge. The search itself is what matters, and finding, which is obviously the goal, often leads to complacency. One feels that Gonzales’ steps are not the stairway to heaven (apologies for the Led Zeppelin reference), but the far more human and relatable struggle to find meaning through learning, and the humble opportunity to pass along the desire to search and grow to the larger social organism.

Pretenderness

When Gonzales’ artist in residence ‘Ninja Pleasure’ (aka Nina Rhode) developed Pianovision for Solo Piano concerts, she created a unique perspective for concert audiences — a top-down view of the piano keyboard that not even the performer sees. Enter the world of YouTube, and Pianovision becomes the perfect medium for presenting Solo Piano compositions in a unique and somewhat disembodied manner. For Solo Piano II, Gonzales’ pre-release teaser videos concentrated on Pianovision perspectives of the songs, and we’re fortunate enough to have the same view for some Solo Piano III songs — including the cleverly-names Pretenderness, which etymologically evokes images of Freddie Mercury’s The Great Pretender, and Elvis’ Love me Tender, but is a classic Gonzales composition. Touching and melancholy, there’s a ‘lilting’ element at play; a light touch by someone who we know can attack the keys with wild abandon.

The process by which a Gonzales composition is ‘christened’ with a title remains a bit of a mystery; sometimes the title provides hints that allude to the piano technique, style, or key, and other times the song title is pure wordplay. Gonzales also speaks of a reductionist approach to music, for example, using a solo piano instead of an orchestra, or playing only two keys in a chord to let listeners’ minds fill in the rest. The point harks back to Einstein’s famous phrase, which suggests keeping complexity to a minimum, but not to the point where something of vital importance is lost. This economy of sound provides a sense of space to the compositions, which allows listeners to connect more deeply with the music, subconsciously completing chords, and filling in gaps with their own thoughts and emotions. Puns must appeal to Gonzales in the same way, as they employ a minimum amount of words to light-up both sides of your brain: first, the left-side understands the language, then the right-side understands the double-meaning. If puns say the most with the least amount of words, then they appear to be the language-based corollary to Gonzales’ approach to solo piano music.

Some time ago, a writer became fascinated with how nicknames for people were selected; the combination of appearance, behaviour, and personality employed to arrive at a succinct (and usually humorous) one or two-word summary of a person’s character. The writer analyzed how he developed nicknames for people in his life — even when he had no idea what their real names were. What really hit home was the punchline: the writer wondered what nicknames other people called him, for he felt those names would reflect his true character far more accurately than his given name. Consciously or subconsciously, Gonzales’ process for naming his songs may be closer to nicknames that reflect the true character of the composition and composer.

Prelude in C-Sharp Major

In The Secrets of Solo Piano III, Gonzales explains that this song is an answer to Bach’s famous Prelude No. 1 in C-Major — a composition so prevalent and iconic, you don’t even hear it as music anymore. One has the sense that Gonzales was interested what makes a piece of music immune to societal, cultural and generational changes and become a global musical connection between people. It’s possible that the role of Charles Gounod’s cover version Ave Maria (complete with an improvised melody) cemented the piece’s societal role through weddings and religious ceremonies. Gonzales’ observation that we don’t hear Bach’s composition as music anymore is fascinating, and hints at the French philosopher Baudrillard’s theory of Simulacra and Simulation.

Simulacra are essentially copies of things that have lost their original. From that point of view, all music prior to modern recording technology is a simulacrum in the sense that we’ve never heard Bach play his composition as he intended it, yet we happily accept that the latest interpretation is indeed representative of the composer’s intentions. Baudrillard’s theory is a bit dark: he felt that our perception of reality has been shaped largely by cultural copies of originals that no longer exist. Think of the mass production of products we purchase and use — they are just copies of an original that no longer exists, or may not have even existed in the first place (in the case of computer-modeled production). For us, the copy replaces the original and is just as real as if we obtained the original itself. Baudrillard then takes his theory even farther and implies that an imitation or simula can be released before the original, and provides an example where war essentially begins when society is convinced that it is coming. Steve Jobs also claimed to know what consumers wanted before they even knew, and could create early hype around products that are now practically an extension of ourselves.

Gonzales may have been applying the idea of injecting modernity into Bach’s now-ubiquitous composition, some 165 years after Gounod’s version, which was itself 137 years after Bach’s original. We can rebuild him, the Six Million Dollar Man quote goes, as Gonzales bumps up the key from C Major to C-Sharp Major, and changes the time signature from 4/4 to 5 beats to the bar. Just past the halfway point, Gonzales adds in an insistent repeated 5-note ‘bell’, followed by a high-register breakdown complete with space, flourishes, rolled chords and hesitation before starting back into the main passage. Gonzales has shaken up a classic and added his interpretation, which we are fortunate enough to hear him play live in concert.

It’s possible that Gonzales’ Prelude in C-Sharp Major will become the de-facto standard that replaces Bach’s (or Gounod’s) version, based on appeal to modern ears. The same could have been said of Charles Gounod’s version, but he likely never imagined that his interpretation would eventually become more popular than the original. Gonzales has set his version free, and whether someone writes lyrics and an improvised melody overtop in 150 years remains to be seen. Regardless, whether digital copy or direct from Gonzales in concert, Prelude in C-Sharp Major is a fantastic take on a classic composition.

Coming Up (comme une fleur)

Although we’ve attended back-to-back concerts in different cities, we’re looking forward to reviewing back-to-back Solo Piano III concerts in Montreal before Gonzales heads back to Europe to continue his tour. Since each concert has its unique moments, it will be interesting to see how the shows differ when the only thing changing is the audience. After that, we’ll continue our in-depth examination of Solo Piano III tracks with Famous Hungarians and the role Liszt (who was Hungarian) played in reviving Hungarian folk music and pushing for modernity in the War of the Romantics.