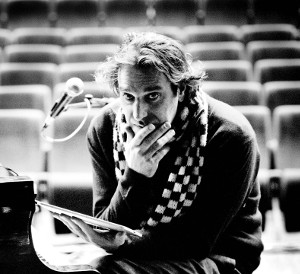

It’s been a hectic day. You’ve finally managed to squeeze into a seat on the train ride home, and press ‘shuffle’ to let the digital gods decide you musical fate. As you stare out the window, your head is filled with the unmistakable first few notes of “Othello”. Instantly, all other sounds disappear and it’s just you and Gonzales’ piano – his music conjuring some fantastic mental images and emotions as the velocity of the train slows down imperceptibly. Great music connects the auditory, visual, and emotional centres of our brain, and Gonzales has refined his craft to create a ‘perfect storm’ of all three. Gonzales is a master sculptor: his medium is sound, and he uses his piano as a tool to chisel away layers to uncover beautiful and unique sculptures that exist within all of us.

It’s been a hectic day. You’ve finally managed to squeeze into a seat on the train ride home, and press ‘shuffle’ to let the digital gods decide you musical fate. As you stare out the window, your head is filled with the unmistakable first few notes of “Othello”. Instantly, all other sounds disappear and it’s just you and Gonzales’ piano – his music conjuring some fantastic mental images and emotions as the velocity of the train slows down imperceptibly. Great music connects the auditory, visual, and emotional centres of our brain, and Gonzales has refined his craft to create a ‘perfect storm’ of all three. Gonzales is a master sculptor: his medium is sound, and he uses his piano as a tool to chisel away layers to uncover beautiful and unique sculptures that exist within all of us.

Sound as Sculpture

When someone mentions the term “sound sculpture”, most people think of a “sound installation” in a modern gallery; an exhibition that combines physical objects and the production of sound to create an intermedia-based art form. While creative and thought-provoking, these displays generally appeal more to our visual sense than auditory, as we are better at consuming data with our eyes as opposed to our ears (blind people notwithstanding). There’s a less common form of sound sculpture in which sounds are manipulated to create a sense of ‘sculpture’ within our minds. One long-running example is Stan Shaff and Doug McEachern’s San Francisco-based Audium – a theatre that has been creating ‘mental sound sculptures’ since 1967 using 176 speakers within a dark auditorium. Some cities, such as Montreal have ‘sound maps’, which are an auditory corollary to photo sites: sounds are uploaded and placed on a map for people to ‘hear’ what different parts of Montreal sounds like over time. These modern examples of using sound as art reinforce the idea that sound can be used to create mental images or sculptures. Travel back a bit further in time, and we discover that the methods of great sculptors have corollaries with the development of great music.

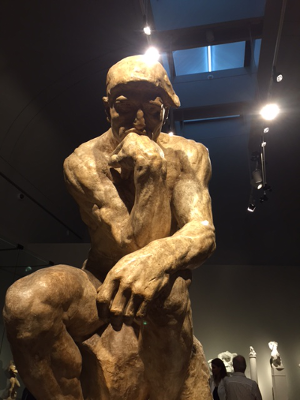

Rodin

Over the summer, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts held an exhibition of the work of the French sculptor Auguste Rodin. Best known for his iconic “The Thinker”, Rodin was a prolific sculptor who pioneered a number of techniques and styles that moved sculpture from a ‘static’ art, to one that captures the fluidity of life. Like many artists (musicians included), Rodin felt that his sculptures were always, “in a state of transition – people only caught a glimpse of a moment in time, moving from one state into the next.” Rodin attributed a large part of his success as a sculptor to his “Assemblage” technique. Rodin would work for weeks, months, and sometime years on perfecting a specific part of the body: limbs, heads, hands, and torsos, which were developed and stored in closets only to be brought about when a sculpture called for a specific idealized part. Paradoxically, ‘remixing’ constituent parts into a beautiful figure served only to further push the boundaries of his sculptures. Paul Gsell wrote of the sculptor Rodin:

Rodin would work for weeks, months, and sometime years on perfecting a specific part of the body: limbs, heads, hands, and torsos, which were developed and stored in closets only to be brought about when a sculpture called for a specific idealized part. Paradoxically, ‘remixing’ constituent parts into a beautiful figure served only to further push the boundaries of his sculptures. Paul Gsell wrote of the sculptor Rodin:

In-between detailed work on larger sculptures, Rodin liked to rapidly shape little figures in clay. These figures were akin to a thought or gesture frozen in time – pieces that revealed a truth in their rapid nature that would otherwise be lost if they were carefully thought out.

Antiquity is my youth, said Rodin whose goal was not to simply copy Greco-Roman art, but to understand their underlying message and bring the message forward for modern eyes. Rodin’s sculptures brought together multiple threads of influences into a new and unique form that inspired a new generation, while still paying homage to past masters. For a sculptor, there is no easy road to success waiting – it is a long struggle.

Gonzales as Sculptor

If you are familiar with Gonzales’ music, you may have been nodding while reading the previous section on Rodin. Gonzales’ music certainly captures a moment in time – built out of small but exquisitely detailed musical gestures that reveal an underlying message. Antiquity may also be Gonzales’ youth, but like Rodin, Gonzales seeks to inspire a new generation by making the techniques of past masters accessible to modern ears. There have also been glimpses that Gonzales also uses an “assemblage” technique. Gonzales explained it very elegantly within past interviews: he doesn’t transcribe or write down his music; if an idea, theme, motif, or melody comes back again and again during his daily ‘noodling’ piano sessions, then maybe the idea is worth exploring. Ideas that don’t return weren’t worth exploring. Apparently, Gonzales stores idealized snippets of music within the recesses his mind, only to be put into practice when the composition requires them.  Alluding back to ‘Othello’, it’s fascinating to hear early vestiges of what would become Othello in a hard-to-find documentary of Gonzales called “In the Corner“. Within the opening title sequence, Gonzales plays an uptempo version of Othello in time with offscreen tap dancing (supposedly from a television show). How long Gonzales was ‘storing’ the theme behind Othello is not apparent, but it would appear that by playing and perfecting the muscle memory behind memorable snippets, Gonzales seems free to add ‘touches’ behind the themes to appeal to our emotions and develop a mental ‘sculpture’ of the song.

Alluding back to ‘Othello’, it’s fascinating to hear early vestiges of what would become Othello in a hard-to-find documentary of Gonzales called “In the Corner“. Within the opening title sequence, Gonzales plays an uptempo version of Othello in time with offscreen tap dancing (supposedly from a television show). How long Gonzales was ‘storing’ the theme behind Othello is not apparent, but it would appear that by playing and perfecting the muscle memory behind memorable snippets, Gonzales seems free to add ‘touches’ behind the themes to appeal to our emotions and develop a mental ‘sculpture’ of the song.

The Universality of Art

“Accidental” discoveries notwithstanding, great things generally take extraordinary people a lifetime to create. In 500 years, Rodin’s “The Thinker” will still be studied as a prime example of a shift in the art of sculpture, while the latest Max Martin-penned hit will more than likely be long forgotten.  Gonzales’ compositions, which have already appeared in music study guides, will continue to be studied and performed representing a link between classical and modern music. Rodin’s sculptures were reduced to a minimum, unencumbered by accessories or objects; Rodin concentrated all his attention on the body and expression of vital tension. Gonzales’ music is also reduced to a minimum; it invites us to develop our own emotions, rather than having an emotive context thrust upon us by a wall of synthesized orchestra. If Rodin’s “The Thinker” is a man symbolizing the universality of reason and the inextricable link between mind and body, then Gonzales’ music symbolizes the universality of music and the link between our auditory faculties and our emotional mind.

Gonzales’ compositions, which have already appeared in music study guides, will continue to be studied and performed representing a link between classical and modern music. Rodin’s sculptures were reduced to a minimum, unencumbered by accessories or objects; Rodin concentrated all his attention on the body and expression of vital tension. Gonzales’ music is also reduced to a minimum; it invites us to develop our own emotions, rather than having an emotive context thrust upon us by a wall of synthesized orchestra. If Rodin’s “The Thinker” is a man symbolizing the universality of reason and the inextricable link between mind and body, then Gonzales’ music symbolizes the universality of music and the link between our auditory faculties and our emotional mind.

Epilogue

As your stop approaches, you take off your earbuds to listen to the sounds of the world around you and begin to plan out the rest of your evening. Maybe Gonzales’ music helped you relax through a miniature fantasy, or maybe he motivated you to find a creative way to solve a difficult problem at work. As you walk through the station, you notice that a teenager is wearing a novelty shirt with “The Thinker” on it. The silhouette of Rodin’s iconic sculpture is shown seated on a toilet with the phrase, S**t Happens in bold letters underneath. You smile to yourself for a moment, then keep moving towards the exit with the rest of the crowd.